ANISTORITON: Essays

Volume 8, March 2004, Section E041

http://www.anistor.co.hol.gr/index.htm

Was ‘Operation Barbarossa’

a reasonable undertaking for 1941 Germany?

by

Dimitrios Kitsos

B.A. (Hist.) M.A. (War Studies)

War Studies Researcher, Assist. Museologist

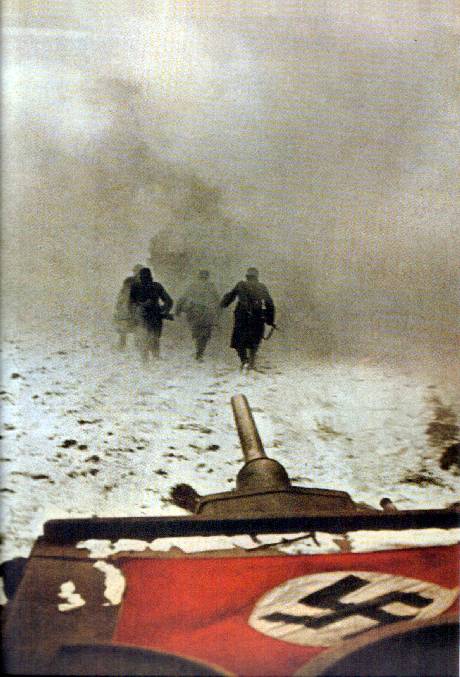

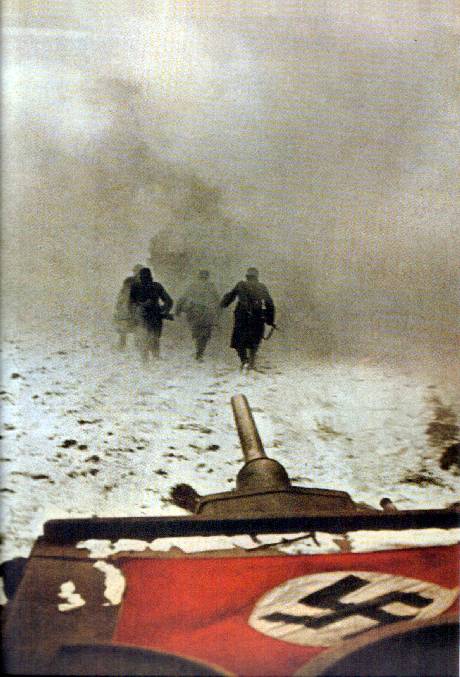

All images come from 1941 German propaganda press.

The battle photos were taken during 'Operation Barbarossa'

Operation Barbarossa began at 3.30 on the morning of 22 June, 1941 when the great German army invaded the Soviet Union. Finally, after a struggle of gigantic proportions that lasted for almost four years, the Soviet flag was raised over the ruined capital of the Reich. This essay deals briefly with the question of whether the Barbarossa offensive was a reasonable undertaking for Germany on the evidence available before June 1941. In order to examine this issue and arrive at a certain conclusion we have to see through German eyes the strengths and the weaknesses of the Red Army and the Wehrmacht before the invasion. Thus, this effort is based mostly on German information, estimations and beliefs, as they have been presented and interpreted by modern historians.

Operation Barbarossa began at 3.30 on the morning of 22 June, 1941 when the great German army invaded the Soviet Union. Finally, after a struggle of gigantic proportions that lasted for almost four years, the Soviet flag was raised over the ruined capital of the Reich. This essay deals briefly with the question of whether the Barbarossa offensive was a reasonable undertaking for Germany on the evidence available before June 1941. In order to examine this issue and arrive at a certain conclusion we have to see through German eyes the strengths and the weaknesses of the Red Army and the Wehrmacht before the invasion. Thus, this effort is based mostly on German information, estimations and beliefs, as they have been presented and interpreted by modern historians.

The sources of information about the Soviet Union were basically the staff of the German embassy in Moscow and a few agents in the neighbouring countries; in addition, radio intercepts and air reconnaissance were used but with limited results.*1 Generally, the Germans had little knowledge of what was expecting them, mostly due to the effective Soviet security measures, but they also made rather poor use of the available data.*2

First of all, the leadership of the Red Army was, quite right, considered to be in a lamentable condition. During 1937 and 1938 thousands of officers, from marshals to company commanders, were executed after Stalin’s orders. So, it was logical to assume that it would take years for the Soviet officer corps to recover. According to a report of the military attach? in Moscow, Lt. General Kostring, in August 1938 ‘the Red Army, owing to the liquidation of a large number of senior officers, who had carried out their tasks very well after ten years of theoretical and practical training, has lost some of its operational-level ability ... The best commanders are gone’. Still, Kostring pointed out that ‘there is no sign and no proof that the fighting ability of the majority has sunk so low that the army is no longer a major factor in any warlike conflict’.*3 His successor, Colonel Crebs, reported with more optimism in early May 1941: ‘Leadership markedly poor (depressing impression). Difference, as compared with 1933, is strikingly negative. Russia will need 20 years to regain the old level’.*4 At about the same time General Blumentritt, comparing the German and Soviet leadership, suggested the following:

The [Soviet] lower-echelon command is schematic, lacking in independence and inflexible. On this point we are far superior! Our subordinate commanders act decisively without fear of taking responsibility. The higher-level command, on the other hand, was always inferior to ours, because it is hesitant, thinks in formal terms, and is mistrustful. The few remaining high-echelon commanders are, with few exceptions, even less of a threat than the earlier, well-trained Tsarist Russian generals.*5

This opinion was held by most members of the German hierarchy and it seemed to be justified by the inadequate Soviet leadership in the war with Finland.*6

Concerning the numerical strength, combat capabilities and generally the quality of the Red Army, the limited or inaccurate information combined with the Nazi ideological conceptions and Wehrmacht’s fresh victories appear to have resulted in extreme optimism and serious underestimation of the enemy. In December 1940, Hitler told his generals: ‘In terms of weapons the Russian soldier is as inferior to us as the French. He has a few modern field batteries, everything else is old, reconditioned material ... the bulk of the Russian panzer force is poorly armoured. The Russian human material is inferior’.*7 In that same year, the Germans estimated that they would have to face 96 infantry divisions, 23 cavalry divisions and 28 mechanised brigades; compared to the battle-hardened German attack force of 110 infantry, 24 panzer, 12 motorised and 1 cavalry divisions it was logical to expect that the enemy would not stand a chance.*8 By June 1941 the calculations of the Soviet strength rose to 154 infantry and 25 cavalry divisions and 37 mechanised brigades;*9 but this was still an underestimation. According to Marshal Zhukov, ‘It is inconceivable that the Germans could have assumed that they were facing at the front a foe with a strength of less than three million men’.*10 In reality, there were almost five million Soviet troops.

Concerning the numerical strength, combat capabilities and generally the quality of the Red Army, the limited or inaccurate information combined with the Nazi ideological conceptions and Wehrmacht’s fresh victories appear to have resulted in extreme optimism and serious underestimation of the enemy. In December 1940, Hitler told his generals: ‘In terms of weapons the Russian soldier is as inferior to us as the French. He has a few modern field batteries, everything else is old, reconditioned material ... the bulk of the Russian panzer force is poorly armoured. The Russian human material is inferior’.*7 In that same year, the Germans estimated that they would have to face 96 infantry divisions, 23 cavalry divisions and 28 mechanised brigades; compared to the battle-hardened German attack force of 110 infantry, 24 panzer, 12 motorised and 1 cavalry divisions it was logical to expect that the enemy would not stand a chance.*8 By June 1941 the calculations of the Soviet strength rose to 154 infantry and 25 cavalry divisions and 37 mechanised brigades;*9 but this was still an underestimation. According to Marshal Zhukov, ‘It is inconceivable that the Germans could have assumed that they were facing at the front a foe with a strength of less than three million men’.*10 In reality, there were almost five million Soviet troops.

The German planners admitted that almost nothing was known about the Red Army’s battle order but insisted that the enemy ‘was unsuited for modern warfare and incapable of decisive resistance against a well-commanded, well-equipped force’.*11 Furthermore, “The Russian national character --slow-wittedness, schematism, fear of responsibility and of taking decisions-- has not changed. The weakness [of the Red Army] lies in the slow-wittedness of the commanders at all levels, the reliance upon stereotyped models, the fact that the training is not up to modern standards, the fear of responsibility and the lack of organisation at all fields.”*12

During the period of partnership between the Wehrmacht and the Red Army in Poland, in late 1939, General Guderian made several reports to Hitler. According to the German leaders, ‘Reports very negative re Soviet weaponry and morale. Armoured vehicles especially old and outdated. Intelligence systems also very backward’.*13 The German General Staff, judging from the Red Army’s performance and materiel in Poland and Finland, concluded that ‘the Russian mass is no match for an Army with modern equipment and superior leadership’.*14 Still, the Germans could have drawn some useful conclusions from the Soviet success against the Japanese in 1939 but they did not pay any attention to the experience of their allies.*15

Regarding the tank forces, the Germans considered that the Soviets had about 10,000 outdated tanks.*16 General Guderian suggested that this number should be put at 17-20,000 and claims that Hitler and the High Command of the Wehrmacht did not believe him then.*17 At any rate, the fact remains that the Germans did not know much about Soviet armour, refused to take into account the rumours concerning new enemy models and believed that they would not have to face anything different from what they had already seen used by the Soviets in Poland and Finland.*18 Consequently, they had a nasty surprise when they encountered the new T-34 tank, which was far superior to all the existing panzers at that time.*19 Yet, the T-34 had first appeared in the battles of Khalkin Gol in 1939 but, as it has been stated, the Germans did not care for the Japanese experience.*20 So, Guderian claimed in May 1941 that: ‘The Russian large armour elements, which have only been in existence since the winter, can thus not yet be ready for action’.*21

The Wehrmacht had assembled for the invasion in June 1941 a force of 3,350 tanks;*22 1,156 of them were the obsolete Marks I and II, 772 were Czech models and only about 1,400 were Marks III and IV. Still, even those latter would prove to be inferior against the new T-34 and KV 1 tanks.*23 Of course, the Germans did not know this but they could have imagined that their 3,350 panzers might be inadequate for an operation like Barbarossa because of the large distances to be covered, the poor state of the roads and the numerical strength of the Soviet tank force, even the underestimated one.*24

The Wehrmacht had assembled for the invasion in June 1941 a force of 3,350 tanks;*22 1,156 of them were the obsolete Marks I and II, 772 were Czech models and only about 1,400 were Marks III and IV. Still, even those latter would prove to be inferior against the new T-34 and KV 1 tanks.*23 Of course, the Germans did not know this but they could have imagined that their 3,350 panzers might be inadequate for an operation like Barbarossa because of the large distances to be covered, the poor state of the roads and the numerical strength of the Soviet tank force, even the underestimated one.*24

The size of the Red Air Force was believed to be about 8-10,000 planes but many of them obsolete.*25 In February 1941, Hitler appeared to have been discouraged for a while by these estimations but he did not revise his plans. The Luftwaffe had approximately 2,700 aircraft available for Barbarossa, which meant an unfavourable ratio of almost 4 to 1.*26 Despite this not very promising counting and the fact that the German planes had to disperse all over a front of more than 1,000 miles there seems to have been no doubt that the Luftwaffe would succeed in its mission.*27 The German calculations would prove to be wrong once again. It is true though that there had been reports suggesting that the number of enemy planes was much larger than it was thought. For example, a Luftwaffe intelligence officer had estimated the total strength of the Red Air Force at about 14,000 planes, a figure that was close to reality.*28 Furthermore, in the spring of 1941 a few Luftwaffe experts had visited some Soviet airplane factories in the Urals and reported that a large-scale program was being executed. Nevertheless, the German supreme command did not take these warnings seriously.*29 Finally, in May 1941 Colonel Crebs reported from Moscow: ‘New fighter. New long-distance bomber. But the performance capacity of the pilots is meagre’.*30

Next, the issue of the Soviet mobilisation capability should also be mentioned. The Germans knew the existence of a para-military organisation called Osoaviakhim which had 36 million members, men and women, and its work was to prepare the civil defence and provide help to the mobilisation machinery. Yet, Hitler rejected the strength and effectiveness of such an organisation;*31 and in September 1940 the High Command of the Army suggested that ‘The Russian command is so clumsy, its use of the Russian railway system so insufficient, that any regrouping will lead to great problems and will thus take longer’.*32 As it would be proven later, the Germans had miscalculated once again.

Concerning the Soviet industrial potential, the information was limited but it was acknowledged by the High Command of the Wehrmacht that the USSR was the third industrial power behind USA and Germany.*33 The Germans had concluded by December 1940 that 32% of the Soviet war production was in the Ukraine, 44% in Moscow and Leningrad and only 24% in the far eastern regions. Consequently, and according to the invasion plans, it was assumed that the German offensive would soon cripple or capture most of the enemy industrial system. Also, it was wrongly believed that the Soviet factory centres and the raw material producing areas were linked only by single-track railways.*34 The Germans did not take into account the few - if any - warnings about the Soviet industries further east. However, in March 1941 it was discovered that one-third of the small arms and artillery as well as 40% of the tank factories were located in the Urals alone. Despite this new information, which meant that much of the enemy war industry would be out of reach, the Germans did not re-assess their plans and continued to think that at any case the Soviet military and industrial system would collapse under the pressure of Barbarossa.*35 Moreover, it was believed that the Red Army would not be able to overcome its transportation and supply problems which, of course, would be worsened by the German invasion.*36

On the other hand, at least some of the German planners had recognised their own industry and supply problems. There had been warnings about shortages in steel, non-ferrous metals and rubber. In February 1941, the High Command of the Wehrmacht was told that ‘aircraft fuel will last until autumn 1941 ... Vehicle fuel only sufficient for the deployment and two months of combat ... The same situation applied to diesel oil’.*37 Still, Hitler did not seem to have bothered about these matters and simply stated that ‘our production is equal to any demand ... our economy is in excellent condition’; and the issue ended there.*38

The Barbarossa plan required swift and large-area operations ant it was recognised that the difficulties in transportation and supply would be greater than ever before. Furthermore, the poor condition of the Soviet roads and the difference in gauge between German and Soviet railways would create additional problems.*39 It is true that some efforts were made regarding these issues. For example, 15,000 Polish light wagons and horses were purchased and 15,000 Poles were hired in order to cope with the problem of the primitive Soviet road network.*40 But generally, the economic and logistic factors of Barbarossa were not regarded by the German leaders as being of such an importance that could delay the planned course of action.*41

The Barbarossa plan required swift and large-area operations ant it was recognised that the difficulties in transportation and supply would be greater than ever before. Furthermore, the poor condition of the Soviet roads and the difference in gauge between German and Soviet railways would create additional problems.*39 It is true that some efforts were made regarding these issues. For example, 15,000 Polish light wagons and horses were purchased and 15,000 Poles were hired in order to cope with the problem of the primitive Soviet road network.*40 But generally, the economic and logistic factors of Barbarossa were not regarded by the German leaders as being of such an importance that could delay the planned course of action.*41

To sum up, according to Leach, the Barbarossa plan

“was based upon a serious underestimation of the strength of the Soviet Union and of the problems presented by its terrain and climate, and upon a crass over-confidence in the invincibility of the Wehrmacht....The economic and logistic factors were almost completely ignored until after the operational plan was completed.”*42

Nevertheless, practically all German military leaders shared Hitler’s belief that Barbarossa would be a short, easy and victorious operation.*43 But this view was not only German; the Allied side had also expressed the same opinion in May/June 1941. The Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Dill, stated that ‘the Germans would go through them like a hot knife through butter’.*44 Other British and American services, officers and politicians believed that the Soviet collapse would be a matter of ten days to three months.*45

So, was Barbarossa a reasonable undertaking for Germany on the evidence available before June 1941? The first thing that one can observe is that there was not much of evidence which guided the planning of the operation. As General Blumentritt admitted, ‘all the information on the Russian army ... is very uncertain and unclear’.*46 The Germans seemed to have replaced knowledge and evidence with estimations and wishful thinking. There is no doubt that the offensive capabilities of the Wehrmacht were really great; there is also no doubt that the Red Army had deficiencies in leadership and equipment. But all these appear to have been dangerously exaggerated by the German planners. Marshal Zhukov was probably right when he said that ‘the German forces invaded the Soviet Union intoxicated by their easy victories over the armies of Western Europe ... and firmly convinced both of the possibility of an easy victory over the Red Army and of their own superiority over all other nations’.*47 Seen in this context of German optimism and limited knowledge of the enemy, Operation Barbarossa appeared reasonable - and not only in German eyes. Even if there had been more accurate information available and less over-confidence, Barbarossa would still seem a quite reasonable undertaking since there were indeed high possibilities of German success. Having in mind the real strength and capabilities of the Wehrmacht and the Red Army, it has been convincingly suggested that the whole idea could be implemented and that Germany could have won. Furthermore, it can be stated that the time of the invasion was the right one. The Soviet Union was not as weak as the Germans estimated but the sure thing is that it would become much stronger in the future if it allied with Britain and USA or if its modernisation remained uninterrupted. Obviously, it would be much more difficult for the Germans to defeat a developed USSR on itself or as a member of an enemy coalition than to believe, as everybody else did, that they really had the power to do it in June 1941. With the Reich master of Europe, Britain isolated and USA still out of the war, the prospects for Barbarossa were very good.*48

At any rate, the main issue about the rationality of Operation Barbarossa in relation to the available information might be summarised in the words of the man behind the decision, the Fuehrer himself. Based mostly on his beliefs and less on concrete evidence, Hitler stated some time before the invasion: ‘You have only to kick in the door and the whole rotten structure will come crushing down’.*49 However, at a later date he said that ‘On the 22nd of June, a door opened before us, and we didn’t know what was behind it ... the heavy uncertainty took me by the throat’.*50

BIBLIOGRAPHY

R. Cecil: Hitler’ s Decision to Invade Russia 1941 (London: Davis - Poynter, 1975)

A. Clark: Barbarossa (London: Hutchinson, 1965)

B. Leach: German Strategy Against Russia, 1939-1941 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973)

R. Lewin: Hitler’s Mistakes (London: Leo Cooper, 1984)

R. Stolfi: Hitler’s Panzers East (Alan Sutton, 1992)

B. Wegner (ed): From Peace to War (Oxford: Berghahn Books, 1997)

G. Weinberg: ‘22 June 1941: The German View’ War in History April 1996

Department of the Army Pamphlet No. 20-261a (1955): The German Campaign in Russia: Planning and Operations (1940-1942)

NOTES

1 The German Campaign in Russia: Planning and Operations (1940-1942):

Department of the Army Pamphlet No. 20-261a, 1955) p.42.

2 B. Leach: German Strategy against Russia, 1939-1941 (Oxford: Clarendon

Press, 1973) pp. 91 & 125, R. Lewin: Hitler’s Mistakes (London: Leo

Cooper, 1984) p. 124

3 B. Wegner (ed): From Peace to War (Oxford: Berghahn Books, 1997) p. 178.

4 R. Cecil: Hitler’s Decision to Invade Russia 1941 (London: Davis-Poynter,

1975) p. 120.

5 Wegner(ed): War p. 182

6 Leach: Strategy p. 92, A. Clark: Barbarossa (London: Hutchinson, 1965) p. 28.

7 Cecil: Decision p. 117.

8 Leach: Strategy p. 92.

9 Leach: ibid. Appendix IV

10 Cecil: Decision p. 122.

11 Wegner (ed): War p. 180.

12 Wegner: ibid. p. 180.

13 Wegner: ibid. p. 181.

14 Cecil: Decision pp. 123-4.

15 Cecil: ibid. pp. 120&124, Clark: Barbarossa p. 30.

16 Leach: Strategy p.172.

17 R. Stolfi: Hitler’s Panzers East (Alan Sutton, 1992) p.238.

18 Leach: Strategy p. 172.

19 Lewin: Mistakes pp. 117, 124.

20 Cecil: Decision p. 121.

21 Wegner (ed): War p. 181.

22 No. 20-261a p. 41.

23 Lewin: Mistakes p. 125.

24 Leach: Strategy p. 98.

25 Leach: ibid. pp. 130, 172.

26 Cecil: Decision pp. 118-9.

27 Leach; Strategy p. 130.

28 Stolfi: Panzers p. 19.

29 No. 20-261a p. 42.

30 Cecil: Decision p. 120. For a detailed presentation of the Red Army’s real

state prior to Barbarossa see Wegner (ed): War pp. 381-394.

31 Clark: Barbarossa p. 34.

32 Wegner (ed): War p. 174.

33 Wegner: ibid. p. 183.

34 Cecil: Decision p. 128.

35 Leach: Strategy pp. 93, 173.

36 Wegner (ed): War p. 183.

37 Leach: Strategy pp. 140, 143.

38 Leach: ibid. p. 142.

39 Leach: ibid. p. 136, Wegner (ed): War p. 208.

40 Stolfi: Panzers p. 18.

41 Wegner (ed): War p. 208, Leach: Strategy p. 130. For an analysis of

the economic planning of Barbarossa see Cecil: Decision pp. 137-151;

for transportation and supply problems before June 1941 see Leach pp.

135-145, Wegner pp. 205-210.

42 Strategy p. 88.

43 G. Weinberg: ‘22 June 1941: The German View’ War in History April

1996, p. 231.

44 Lewin: Mistakes p. 120.

45 Wegner (ed): War p. 184.

46 Wegner (ed): ibid. p. 182.

47 Cecil: Decision pp. 129-130.

48 Stolfi: Panzers pp. 15-25, Lewin: Mistakes p. 120.

49 Clark: Barbarossa p. 34.

50 Cecil: Decision p. 136.

Operation Barbarossa began at 3.30 on the morning of 22 June, 1941 when the great German army invaded the Soviet Union. Finally, after a struggle of gigantic proportions that lasted for almost four years, the Soviet flag was raised over the ruined capital of the Reich. This essay deals briefly with the question of whether the Barbarossa offensive was a reasonable undertaking for Germany on the evidence available before June 1941. In order to examine this issue and arrive at a certain conclusion we have to see through German eyes the strengths and the weaknesses of the Red Army and the Wehrmacht before the invasion. Thus, this effort is based mostly on German information, estimations and beliefs, as they have been presented and interpreted by modern historians.

Operation Barbarossa began at 3.30 on the morning of 22 June, 1941 when the great German army invaded the Soviet Union. Finally, after a struggle of gigantic proportions that lasted for almost four years, the Soviet flag was raised over the ruined capital of the Reich. This essay deals briefly with the question of whether the Barbarossa offensive was a reasonable undertaking for Germany on the evidence available before June 1941. In order to examine this issue and arrive at a certain conclusion we have to see through German eyes the strengths and the weaknesses of the Red Army and the Wehrmacht before the invasion. Thus, this effort is based mostly on German information, estimations and beliefs, as they have been presented and interpreted by modern historians. Concerning the numerical strength, combat capabilities and generally the quality of the Red Army, the limited or inaccurate information combined with the Nazi ideological conceptions and Wehrmacht’s fresh victories appear to have resulted in extreme optimism and serious underestimation of the enemy. In December 1940, Hitler told his generals: ‘In terms of weapons the Russian soldier is as inferior to us as the French. He has a few modern field batteries, everything else is old, reconditioned material ... the bulk of the Russian panzer force is poorly armoured. The Russian human material is inferior’.*7 In that same year, the Germans estimated that they would have to face 96 infantry divisions, 23 cavalry divisions and 28 mechanised brigades; compared to the battle-hardened German attack force of 110 infantry, 24 panzer, 12 motorised and 1 cavalry divisions it was logical to expect that the enemy would not stand a chance.*8 By June 1941 the calculations of the Soviet strength rose to 154 infantry and 25 cavalry divisions and 37 mechanised brigades;*9 but this was still an underestimation. According to Marshal Zhukov, ‘It is inconceivable that the Germans could have assumed that they were facing at the front a foe with a strength of less than three million men’.*10 In reality, there were almost five million Soviet troops.

Concerning the numerical strength, combat capabilities and generally the quality of the Red Army, the limited or inaccurate information combined with the Nazi ideological conceptions and Wehrmacht’s fresh victories appear to have resulted in extreme optimism and serious underestimation of the enemy. In December 1940, Hitler told his generals: ‘In terms of weapons the Russian soldier is as inferior to us as the French. He has a few modern field batteries, everything else is old, reconditioned material ... the bulk of the Russian panzer force is poorly armoured. The Russian human material is inferior’.*7 In that same year, the Germans estimated that they would have to face 96 infantry divisions, 23 cavalry divisions and 28 mechanised brigades; compared to the battle-hardened German attack force of 110 infantry, 24 panzer, 12 motorised and 1 cavalry divisions it was logical to expect that the enemy would not stand a chance.*8 By June 1941 the calculations of the Soviet strength rose to 154 infantry and 25 cavalry divisions and 37 mechanised brigades;*9 but this was still an underestimation. According to Marshal Zhukov, ‘It is inconceivable that the Germans could have assumed that they were facing at the front a foe with a strength of less than three million men’.*10 In reality, there were almost five million Soviet troops. The Wehrmacht had assembled for the invasion in June 1941 a force of 3,350 tanks;*22 1,156 of them were the obsolete Marks I and II, 772 were Czech models and only about 1,400 were Marks III and IV. Still, even those latter would prove to be inferior against the new T-34 and KV 1 tanks.*23 Of course, the Germans did not know this but they could have imagined that their 3,350 panzers might be inadequate for an operation like Barbarossa because of the large distances to be covered, the poor state of the roads and the numerical strength of the Soviet tank force, even the underestimated one.*24

The Wehrmacht had assembled for the invasion in June 1941 a force of 3,350 tanks;*22 1,156 of them were the obsolete Marks I and II, 772 were Czech models and only about 1,400 were Marks III and IV. Still, even those latter would prove to be inferior against the new T-34 and KV 1 tanks.*23 Of course, the Germans did not know this but they could have imagined that their 3,350 panzers might be inadequate for an operation like Barbarossa because of the large distances to be covered, the poor state of the roads and the numerical strength of the Soviet tank force, even the underestimated one.*24 The Barbarossa plan required swift and large-area operations ant it was recognised that the difficulties in transportation and supply would be greater than ever before. Furthermore, the poor condition of the Soviet roads and the difference in gauge between German and Soviet railways would create additional problems.*39 It is true that some efforts were made regarding these issues. For example, 15,000 Polish light wagons and horses were purchased and 15,000 Poles were hired in order to cope with the problem of the primitive Soviet road network.*40 But generally, the economic and logistic factors of Barbarossa were not regarded by the German leaders as being of such an importance that could delay the planned course of action.*41

The Barbarossa plan required swift and large-area operations ant it was recognised that the difficulties in transportation and supply would be greater than ever before. Furthermore, the poor condition of the Soviet roads and the difference in gauge between German and Soviet railways would create additional problems.*39 It is true that some efforts were made regarding these issues. For example, 15,000 Polish light wagons and horses were purchased and 15,000 Poles were hired in order to cope with the problem of the primitive Soviet road network.*40 But generally, the economic and logistic factors of Barbarossa were not regarded by the German leaders as being of such an importance that could delay the planned course of action.*41