Issue E991 of 6 January 1999

GLADIVS versus SARISSA

Roman legions against Greek pike phalanx

Rest your mouse pointer on the images below to view their descriptions

by

Dimitrios Kitsos

B.A. (Hist.)

M.A. (War Stud.)

During the first half of the 2nd century BC the Roman legion confronted the Macedonian phalanx. In most of the engagements - including the major ones at Cynoscephalae, Magnesia and Pydna - the Romans prevailed over their opponents and the Republic emerged as the indisputable Mediterranean power. This essay deals with the causes of the Roman military successes by examining briefly the Macedonian and Roman systems of war and searching for possible other factors that contributed to the defeat of the phalanx. The focus of this effort will be the battles of Cynoscephalae and Pydna. For a number of reasons, Magnesia is not going to be treated here. The ancient accounts are considered to be completely fantastic and it is argued that the army of Antiochus III did not have a pure sarissa phalanx formation.1 It is also suggested that the outcome was determined mostly by the action of the Pergamene cavalry of king Eumenes, a Roman ally, and not by an actual clash between the legion and whatever kind of phalanx Antiochus employed at Magnesia.2 Besides, the study of the Roman victories against Philip V and Perseus is more than sufficient for our purpose, given also the space limitation.

First of all, let's have a look at the effectiveness of the weapons and tactics used by the phalanx and the legion during the period of their confrontation. The main weapon of the phalangite was the sarissa, a spear which by that time extended up to 21 feet and it was held with both hands. According to Polybius, all the sarissae had the same length.3 Still, it has been suggested that the first four ranks of the phalanx were equipped with shorter spears of various lengths, from 9 to 18 feet, and that the 21-foot sarissae were carried by the additional twelve ranks.4 At any rate, the fact remains that the sarissa had a really long reach and could pierce the shields and breastplates of the legionaries who stood on its way, as it happened at Pydna.5 On the other hand, the sarissa was obviously a heavy and unwieldy weapon, unsuitable for fighting man to man;6 for this purpose the phalangites had a small sword.7 The men on the front lines carried shields but those at the rear most probably had either no shields at all or small and light ones slung across their chests;8 however, they proved to be inadequate protection against the Roman sword.9 This brings us to the next issue, Roman weaponry.

First of all, let's have a look at the effectiveness of the weapons and tactics used by the phalanx and the legion during the period of their confrontation. The main weapon of the phalangite was the sarissa, a spear which by that time extended up to 21 feet and it was held with both hands. According to Polybius, all the sarissae had the same length.3 Still, it has been suggested that the first four ranks of the phalanx were equipped with shorter spears of various lengths, from 9 to 18 feet, and that the 21-foot sarissae were carried by the additional twelve ranks.4 At any rate, the fact remains that the sarissa had a really long reach and could pierce the shields and breastplates of the legionaries who stood on its way, as it happened at Pydna.5 On the other hand, the sarissa was obviously a heavy and unwieldy weapon, unsuitable for fighting man to man;6 for this purpose the phalangites had a small sword.7 The men on the front lines carried shields but those at the rear most probably had either no shields at all or small and light ones slung across their chests;8 however, they proved to be inadequate protection against the Roman sword.9 This brings us to the next issue, Roman weaponry.

The main weapon of the legionary was the so-called Spanish sword (gladius), excellent for thrusting and hacking since its double-edged blade was very strong and firm.10 Livy describes very vividly the horrible wounds inflicted by the gladius and the shock of Philip's troops when they saw the maimed bodies of their dead comrades.11 The Roman soldier was armed also with a couple of special javelins (pila), a light and a heavy one; both of them were thrown against the enemy before contact was made. If it did not kill, the pilum could pierce a shield and, due to its design and construction, render it virtually useless.12 Concerning defensive equipment, the most important piece for the legionary was his large rectangular shield (scutum). The scutum left no parts of the body exposed and offered a high degree of protection against Macedonian arrows and short swords but not against sarissae, as it has been mentioned.13

The main weapon of the legionary was the so-called Spanish sword (gladius), excellent for thrusting and hacking since its double-edged blade was very strong and firm.10 Livy describes very vividly the horrible wounds inflicted by the gladius and the shock of Philip's troops when they saw the maimed bodies of their dead comrades.11 The Roman soldier was armed also with a couple of special javelins (pila), a light and a heavy one; both of them were thrown against the enemy before contact was made. If it did not kill, the pilum could pierce a shield and, due to its design and construction, render it virtually useless.12 Concerning defensive equipment, the most important piece for the legionary was his large rectangular shield (scutum). The scutum left no parts of the body exposed and offered a high degree of protection against Macedonian arrows and short swords but not against sarissae, as it has been mentioned.13

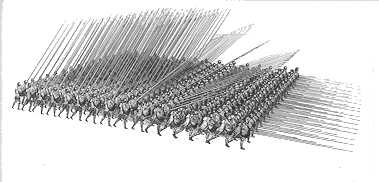

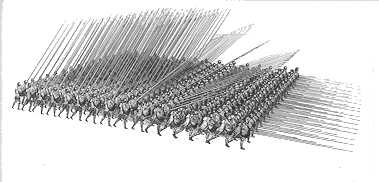

According to Plutarch, the Roman consul Aemilius Paulus was terrified by the sight of the phalanx charging and sweeping everything before it at Pydna.14 It appears that the phalanx of the 2nd century BC was tightened up more than the original Macedonian phalanx and it was equipped with longer sarissae. The Macedonian battle formation was usually 16 men deep; the first five ranks had their sarissae levelled while the rest held them elevated so as to keep off the incoming missiles. In the close battle order of this later phalanx each man occupied half the width of a Roman soldier in formation. Thus, in a frontal attack one legionary had to face two phalangites and ten sarissae simultaneously;15 '... and it is both impossible for a single man to cut through them all in time once they are at close quarters and by no means easy to force their points away'.16 Another advantage of the phalanx was that - apart from the first and the rear ranks - it could be composed of half-trained men who just held their sarissae and pushed.17 So, it is obvious that the sarissa phalanx was a tight formation based on mass shock action and not on individual fighting. On the other hand, the Romans relied on tactical flexibility and skilled swordsmanship.

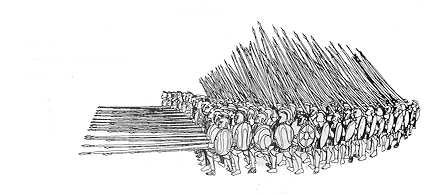

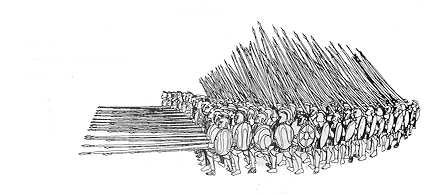

The legion of the Macedonian wars had a strength of 4,200 infantry and 300 cavalry. The light-armed troops (velites) numbered about 1,200. The heavy infantry was deployed in three successive lines, each one composed of a different kind of legionary. The 1,200 men on the front were the less heavily armored hastati; next came the 1,200 principes who were the best swordsmen of young age while the older soldiers, the 600 triarii, were placed at the back. The legion was broken up into smaller tactical units, the maniples, each one consisting of 120 men - except the maniples of the triarii which were 60 men strong. There were 30 maniples of heavy infantry in every legion positioned with intervals between them and arranged in a chequerboard formation; thus, each maniple covered the gap of the line in front of it. Usually, the legion marched into battle in this way.18

The legion of the Macedonian wars had a strength of 4,200 infantry and 300 cavalry. The light-armed troops (velites) numbered about 1,200. The heavy infantry was deployed in three successive lines, each one composed of a different kind of legionary. The 1,200 men on the front were the less heavily armored hastati; next came the 1,200 principes who were the best swordsmen of young age while the older soldiers, the 600 triarii, were placed at the back. The legion was broken up into smaller tactical units, the maniples, each one consisting of 120 men - except the maniples of the triarii which were 60 men strong. There were 30 maniples of heavy infantry in every legion positioned with intervals between them and arranged in a chequerboard formation; thus, each maniple covered the gap of the line in front of it. Usually, the legion marched into battle in this way.18

After skirmishing, the velites withdrew through the intervals between the maniples and regrouped behind the triarii. Then, the 10 maniples of the hastati came forward and formed a solid line; the legionaries hurled their pila, drew their swords and came to grips with their opponents, trying to exploit gaps in the enemy formation. If the hastati failed to breakthrough, they disengaged and retired through the 10 maniples of the principes. In their turn, the principes formed a solid line and attacked with pila and swords. If the enemy still held its ground, the principes were relieved similarly by the 10 maniples of the triarii. So, the legion kept its adversary under constant pressure by fresh troops. Depending on the circumstances this standard procedure, as well as the width, depth and disposition of the maniples, could be modified.19

Finally, both Macedonians and Romans used cavalry and/or allied troops to cover their flanks, as it is reported by the ancient accounts.

After this basic outline of the Macedonian and Roman fighting methods, a summary of the two great battles which virtually ended the effective military history of the phalanx is necessary. After some minor operations, the decisive battle of the 2nd Macedonian war took place in May 197 BC in Thessaly. King Philip V of Macedon had an army of approximately 16,000 phalangites, 7,500 other infantry and 2,000 cavalry. The Roman side, under the command of consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus, numbered about 18,000 Roman and Italian troops, 8,000 Greek allies - most of them Aetolians - 2,400 Roman, Italian and Aetolian cavalrymen and 20 elephants.

In a thick mist, the advanced forces of the opposing armies met each other unexpectedly on the Cynoscephalae hills. Both commanders sent reinforcements and the reconnaissance skirmish soon developed into a full-scale engagement. Philip, despite the unfavourable terrain and the fact that he had sent many of his men to collect fodder, accepted battle after receiving encouraging messages from the front line. The king, leading on the right wing the half of his phalanx that had formed up, charged downhill and pushed back the Roman left. Yet, Flamininus saw that most of the Macedonians on the left were still in marching order uphill or trying to deploy and immediately launched an attack with his right flank and the elephants against them. The disordered Macedonian left broke easily and fled pursued by Romans and Aetolians. In the meantime, the Roman left was being hardly pressed by the advancing phalanx. Then, an unknown tribune took 20 maniples from the victorious right flank and attacked the Macedonian right from the rear; the exposed phalangites suffered heavy casualties and they were finally routed. The Macedonians lost about 8,000 dead and 5,000 prisoners while the Roman side had 700 killed.20 This was the first time that the sarissa phalanx was defeated by the legion in a pitched battle.

Concerning the battle of Pydna not much is known from our ancient sources but possibly things happened as follows. The strength of king Perseus' army is estimated at 20,000 phalangites, 17,000 other infantry, an elite agema of 3,000 men and 4,000 cavalry. On the other side, consul Lucius Aemilius Paulus had at his disposal a force of about 37,000 Romans, Italians, Pergamenes and Numidians plus 34 elephants. In June 168 BC the two armies were met at Pydna in southern Macedonia and the fighting began accidentally over a stream.

Initially, the charge of the phalanx was irresistible. The Macedonians advanced swiftly and after some fierce fighting the Romans made an orderly retreat towards rough ground. When the pursuing phalanx entered that area, it started to lose its cohesion and gaps were created in its long line. Realising this, Paulus ordered his legionaries to infiltrate in small groups wherever possible and fight many single combats at close quarters; thus, the phalanx gradually disintegrated. In the meantime, the Roman right had managed with a counter-attack supported by elephants to break the enemy left. On the other wing, Perseus with the main body of his cavalry had already fled. The remaining phalangites, being attacked now by all sides, were slaughtered; the 3,000 picked troops of the agema fell fighting to the last man. Within an hour everything was over. According to the sources the Macedonian losses were enormous, 20,000 killed and 11,000 captured. The Romans had only 100 dead.21

Concerning the battle of Pydna not much is known from our ancient sources but possibly things happened as follows. The strength of king Perseus' army is estimated at 20,000 phalangites, 17,000 other infantry, an elite agema of 3,000 men and 4,000 cavalry. On the other side, consul Lucius Aemilius Paulus had at his disposal a force of about 37,000 Romans, Italians, Pergamenes and Numidians plus 34 elephants. In June 168 BC the two armies were met at Pydna in southern Macedonia and the fighting began accidentally over a stream.

Initially, the charge of the phalanx was irresistible. The Macedonians advanced swiftly and after some fierce fighting the Romans made an orderly retreat towards rough ground. When the pursuing phalanx entered that area, it started to lose its cohesion and gaps were created in its long line. Realising this, Paulus ordered his legionaries to infiltrate in small groups wherever possible and fight many single combats at close quarters; thus, the phalanx gradually disintegrated. In the meantime, the Roman right had managed with a counter-attack supported by elephants to break the enemy left. On the other wing, Perseus with the main body of his cavalry had already fled. The remaining phalangites, being attacked now by all sides, were slaughtered; the 3,000 picked troops of the agema fell fighting to the last man. Within an hour everything was over. According to the sources the Macedonian losses were enormous, 20,000 killed and 11,000 captured. The Romans had only 100 dead.21

Regarding the causes of the Roman victories, Polybius wrote in his classical comment on Macedonian and Roman tactics that nothing could withstand the frontal charge of the phalanx as long as it preserved its characteristic formation.22 However,

' ... it is acknowledged that the phalanx requires level and clear ground with no obstacles such as ditches, clefts, clumps of trees, ridges and water courses, all of which are sufficient to impede and break up such a formation .... the Romans do not make their line equal in force to the enemy and expose all the legions to a frontal attack by the phalanx, but part of their forces remain in reserve and the rest engage the enemy. Afterwards whether the phalanx drives back by its charge the force opposed to it or is repulsed by this force, its own peculiar formation is broken up. For either in following a retreating foe or in flying before an attacking foe, they leave behind the other parts of their own army, upon which the enemy's reserve have room enough in the space formerly held by the phalanx to attack no longer in front but appearing by a lateral movement on the flank and rear of the phalanx .... the Macedonian formation is at times of little use and at times of no use at all, because the phalanx soldier can be of service neither in detachments nor singly, while the Roman formation is efficient. For every Roman soldier, once he is armed and sets about his business, can adapt himself equally well to every place and time and can meet attack from every quarter . He is likewise equally prepared and equally in condition whether he has to fight together with the whole army or with a part of it or in maniples or singly'.23

In this way Polybius clearly presented what was most likely to happen in every encounter between phalanx and legion. Having in mind the accounts of the battles at Cynoscephalae and Pydna, it is easy to understand that things happened exactly as Polybius had pointed out. The frontal assault of a coherent phalanx was devastating but in rough and uneven ground this formation could not work. Philip's left wing did not manage to form up in time and Perseus' entire phalanx was disordered because of the terrain. On the contrary, the manipular system enabled the legion to operate much more easily and disperse its attacks. The massive and cumbersome Macedonian formation was unable to protect itself when it was attacked on the flank or the rear by independently acting maniples and at close quarters the phalangites were generally no match for the better equipped and trained Roman swordsman.24

Another major factor that contributed to the defeat of the phalanx was the inadequate flank protection by the cavalry force. In contrast to earlier glorious periods, the Macedonians had neglected their cavalry and relied mostly on the sarissa phalanx, trying to maximize its shock action but not taking into account the disadvantages. It is surprising to see that Philip had only 2,000 troopers, half of them Macedonians, against an enemy which counted on maneuverability and outflanking in order to deal with the phalanx; on the contrary, it was the Roman and allied cavalry that proved to be superior. It is argued that, most possibly, the outcome of the wars would have been different if there had been a strong and efficient Macedonian cavalry force.25

The help of the allies in the Roman victories should also be mentioned. As it has been stated, much of the Roman army was composed of Greek, Italian or other troops. They provided an additional manpower used for a variety of purposes but especially concerning cavalry their contribution had been crucial. For example, the Aetolian troopers at Cynoscephalae performed excellently and prevented a general rout of the advanced Roman forces.26

Next, the elephants seem to have played an important role at the two great battles, smashing through the Macedonian left wing at Cynoscephalae and pushing back the enemy cavalry at Pydna before they were joined in the attack by the Roman forces that routed Perseus' left flank.27 The action of the elephants at those instances resulted in the opportunities that the legionaries awaited for and fully exploited, that is, gaps in the Macedonian line and the right conditions for outflanking.

Last but not least, the issue of leadership. It appears that in this aspect too the Romans had an advantage. Philip, although he had realized that neither the place nor the time were suitable, finally made the fatal mistake to engage with only part of his force at Cynoscephalae in order to support his skirmishers28 Furthermore, the phalangites on the left flank tried to catch up with the rest of the charging army 'having no one to give them orders'.29 This incident clearly indicates a break in the Macedonian chain of command. On the other hand, with the 'brilliant initiative of the military tribune' who hit the phalanx at the rear the Romans won a total victory.30 Finally, Perseus seems to have lost control of his army at Pydna and fled early in the battle; his overall performance was lamentable compared to the competence and bravery displayed by Aemilius Paulus.31

Last but not least, the issue of leadership. It appears that in this aspect too the Romans had an advantage. Philip, although he had realized that neither the place nor the time were suitable, finally made the fatal mistake to engage with only part of his force at Cynoscephalae in order to support his skirmishers28 Furthermore, the phalangites on the left flank tried to catch up with the rest of the charging army 'having no one to give them orders'.29 This incident clearly indicates a break in the Macedonian chain of command. On the other hand, with the 'brilliant initiative of the military tribune' who hit the phalanx at the rear the Romans won a total victory.30 Finally, Perseus seems to have lost control of his army at Pydna and fled early in the battle; his overall performance was lamentable compared to the competence and bravery displayed by Aemilius Paulus.31

To sum up, the inherent weaknesses of the later Macedonian phalanx, the more flexible Roman tactics and better armament for hand to hand combat combined with the allied help, the effective use of elephants, the superiority in cavalry and the successful high and lower command resulted in the victory of the legion over the phalanx. It was time for a new master.

ANCIENT SOURCES

Titus Livius: Books XXXI-XLV.

Plutarch: Flamininus.

Plutarch: Aemilius Paulus.

Polybius: The Histories.

MODERN WORKS

F. Adcock: The Roman Art of War Under the Republic (Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons Ltd, 1963)

H. Delbruck: History of the Art of War trn. by W. Renfroe (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1975)

N. Hammond: 'The Campaign and Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC' Journal of Hellenic Studies 108 (1988)

N. Hammond: 'The Battle of Pydna' Journal of Hellenic Studies 104 (1984)

D. Head: Armies of the Macedonian and Punic Wars (Wargames Research Publication, 1982)

A. Jones: The Art of War in the Western World (London: Harrap, 1988)

G. Parker (ed): The Cambridge Illustrated History of Warfare (Cambridge University Press, 1995)

N. Sekunda: Republican Roman Army, 200-104 BC (London: Osprey, 1996)

W. Tarn: Hellenistic Military & Naval Developments (Cambridge University Press, 1930)

J. Warry: Warfare in the Classical World (London: Salamander, 1980)

NOTES

1 H. Delbruck: History of the Art of War trn. by W. Renfroe (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1975) pp. 397, 399.

2 F. Adcock: The Roman Art of War Under the Republic (Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons Ltd, 1963) p. 110, A. Jones: The Art of War in the Western World (London: Harrap, 1988) p. 33, W. Tarn: Hellenistic Military & Naval Developments (Cambridge University Press, 1930) p. 29.

3 Polybius: The Histories trn. by W. Paton (London: Heinemann, 1960) XVIII. 29.

4 Delbruck: History pp. 394 - 5, Jones: Art p. 33.

5 Plutarch: Aemilius Paulus trn. by B. Perrin (London: Heinemann, 1928) 20.

6 Plutarch: Flamininus trn. by B. Perrin (London: Heinemann, 1921) 8.

7 J. Warry: Warfare in the Classical World (London: Salamander, 1980) p. 125, D. Head: Armies of the Macedonian and Punic Wars (Wargames Research Publication, 1982) p. 111, N. Hammond: 'The Battle of Pydna' Journal of Hellenic Studies 104 (1984) p. 46.

8 Jones: Art p. 33, Head: Armies p. 111.

9 Plutarch: Aemilius Paulus 20.

10 N. Sekunda: Republican Roman Army (London: Osprey, 1996) pp. 9-10, G. Parker (ed): The Cambridge Illustrated History of Warfare (Cambridge University Press, 1995) p. 45.

11 Livy: Books XXXI-XLV trn. by H. Bettenson (Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1983) XXXI. 34.

12 Sekunda: Republican p. 9, Head: Armies p. 157.

13 Livy: XXXI. 39, Plutarch: Aemilius Paulus 20, Head: Armies p. 158. For a detailed description of Macedonian and Roman infantry equipment see Sekunda pp. 4-10, Head pp. 47-8, 156-8.

14 Aemilius Paulus 19.

15 Delbruck: History pp. 395-7, Jones: Art p. 33, Warry: Warfare p. 125.

16 Polybius: XVIII. 30.

17 Tarn: Hellenistic p. 28.

18 Sekunda: Republican pp. 14-15, 19, 35, Head: Armies pp. 39, 58.

19 Parker (ed): Cambridge pp. 46-7, Head: Armies pp 58-9, Sekunda: Republican pp. 21-3, 34-5.

20 Polybius: XVIII. 18-27, Livy: XXXIII. 3-10, Plutarch: Flamininus 8, Head: Armies p. 81, N. Hammond: 'The Campaign and the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC' Journal of Hellenic Studies 108 (1988) pp. 72-6.

21 Livy: XLIV. 40-43, Plutarch: Aemilius Paulus 18-23, Hammond: 'Pydna' pp. 39-47, Head: Armies p. 83.

22 Polybius: XVIII. 30.

23 Polybius: XVIII. 31-32. See also Plutarch: Flamininus 8.

24 Parker (ed): Cambridge p. 47, Head: Armies pp. 47, 59, Warry: Warfare pp. 125-6.

25 Sekunda:Republican p. 41, Tarn: Hellenistic pp. 27-9.

26 Polybius: XVIII. 22, Livy: XXXIII. 8.

27 Polybius: XVIII. 25, Livy: XXXIII. 9, XLIV. 41.

28 Polybius: XVIII. 22, Livy: XXXIII. 8, Hammond: 'Cynoscephalae' p. 76.

29 Polybius: XVIII. 25.

30 Hammond: 'Cynoscephalae' p. 76.

31 Hammond: 'Pydna' pp. 46-7, Adcock: Roman p. 110.

Back to Cover

Back to Cover

This page hosted by

Get your own Free Home Page

Get your own Free Home Page

First of all, let's have a look at the effectiveness of the weapons and tactics used by the phalanx and the legion during the period of their confrontation. The main weapon of the phalangite was the sarissa, a spear which by that time extended up to 21 feet and it was held with both hands. According to Polybius, all the sarissae had the same length.3 Still, it has been suggested that the first four ranks of the phalanx were equipped with shorter spears of various lengths, from 9 to 18 feet, and that the 21-foot sarissae were carried by the additional twelve ranks.4 At any rate, the fact remains that the sarissa had a really long reach and could pierce the shields and breastplates of the legionaries who stood on its way, as it happened at Pydna.5 On the other hand, the sarissa was obviously a heavy and unwieldy weapon, unsuitable for fighting man to man;6 for this purpose the phalangites had a small sword.7 The men on the front lines carried shields but those at the rear most probably had either no shields at all or small and light ones slung across their chests;8 however, they proved to be inadequate protection against the Roman sword.9 This brings us to the next issue, Roman weaponry.

First of all, let's have a look at the effectiveness of the weapons and tactics used by the phalanx and the legion during the period of their confrontation. The main weapon of the phalangite was the sarissa, a spear which by that time extended up to 21 feet and it was held with both hands. According to Polybius, all the sarissae had the same length.3 Still, it has been suggested that the first four ranks of the phalanx were equipped with shorter spears of various lengths, from 9 to 18 feet, and that the 21-foot sarissae were carried by the additional twelve ranks.4 At any rate, the fact remains that the sarissa had a really long reach and could pierce the shields and breastplates of the legionaries who stood on its way, as it happened at Pydna.5 On the other hand, the sarissa was obviously a heavy and unwieldy weapon, unsuitable for fighting man to man;6 for this purpose the phalangites had a small sword.7 The men on the front lines carried shields but those at the rear most probably had either no shields at all or small and light ones slung across their chests;8 however, they proved to be inadequate protection against the Roman sword.9 This brings us to the next issue, Roman weaponry. The main weapon of the legionary was the so-called Spanish sword (gladius), excellent for thrusting and hacking since its double-edged blade was very strong and firm.10 Livy describes very vividly the horrible wounds inflicted by the gladius and the shock of Philip's troops when they saw the maimed bodies of their dead comrades.11 The Roman soldier was armed also with a couple of special javelins (pila), a light and a heavy one; both of them were thrown against the enemy before contact was made. If it did not kill, the pilum could pierce a shield and, due to its design and construction, render it virtually useless.12 Concerning defensive equipment, the most important piece for the legionary was his large rectangular shield (scutum). The scutum left no parts of the body exposed and offered a high degree of protection against Macedonian arrows and short swords but not against sarissae, as it has been mentioned.13

The main weapon of the legionary was the so-called Spanish sword (gladius), excellent for thrusting and hacking since its double-edged blade was very strong and firm.10 Livy describes very vividly the horrible wounds inflicted by the gladius and the shock of Philip's troops when they saw the maimed bodies of their dead comrades.11 The Roman soldier was armed also with a couple of special javelins (pila), a light and a heavy one; both of them were thrown against the enemy before contact was made. If it did not kill, the pilum could pierce a shield and, due to its design and construction, render it virtually useless.12 Concerning defensive equipment, the most important piece for the legionary was his large rectangular shield (scutum). The scutum left no parts of the body exposed and offered a high degree of protection against Macedonian arrows and short swords but not against sarissae, as it has been mentioned.13  The legion of the Macedonian wars had a strength of 4,200 infantry and 300 cavalry. The light-armed troops (velites) numbered about 1,200. The heavy infantry was deployed in three successive lines, each one composed of a different kind of legionary. The 1,200 men on the front were the less heavily armored hastati; next came the 1,200 principes who were the best swordsmen of young age while the older soldiers, the 600 triarii, were placed at the back. The legion was broken up into smaller tactical units, the maniples, each one consisting of 120 men - except the maniples of the triarii which were 60 men strong. There were 30 maniples of heavy infantry in every legion positioned with intervals between them and arranged in a chequerboard formation; thus, each maniple covered the gap of the line in front of it. Usually, the legion marched into battle in this way.18

The legion of the Macedonian wars had a strength of 4,200 infantry and 300 cavalry. The light-armed troops (velites) numbered about 1,200. The heavy infantry was deployed in three successive lines, each one composed of a different kind of legionary. The 1,200 men on the front were the less heavily armored hastati; next came the 1,200 principes who were the best swordsmen of young age while the older soldiers, the 600 triarii, were placed at the back. The legion was broken up into smaller tactical units, the maniples, each one consisting of 120 men - except the maniples of the triarii which were 60 men strong. There were 30 maniples of heavy infantry in every legion positioned with intervals between them and arranged in a chequerboard formation; thus, each maniple covered the gap of the line in front of it. Usually, the legion marched into battle in this way.18 Concerning the battle of Pydna not much is known from our ancient sources but possibly things happened as follows. The strength of king Perseus' army is estimated at 20,000 phalangites, 17,000 other infantry, an elite agema of 3,000 men and 4,000 cavalry. On the other side, consul Lucius Aemilius Paulus had at his disposal a force of about 37,000 Romans, Italians, Pergamenes and Numidians plus 34 elephants. In June 168 BC the two armies were met at Pydna in southern Macedonia and the fighting began accidentally over a stream.

Initially, the charge of the phalanx was irresistible. The Macedonians advanced swiftly and after some fierce fighting the Romans made an orderly retreat towards rough ground. When the pursuing phalanx entered that area, it started to lose its cohesion and gaps were created in its long line. Realising this, Paulus ordered his legionaries to infiltrate in small groups wherever possible and fight many single combats at close quarters; thus, the phalanx gradually disintegrated. In the meantime, the Roman right had managed with a counter-attack supported by elephants to break the enemy left. On the other wing, Perseus with the main body of his cavalry had already fled. The remaining phalangites, being attacked now by all sides, were slaughtered; the 3,000 picked troops of the agema fell fighting to the last man. Within an hour everything was over. According to the sources the Macedonian losses were enormous, 20,000 killed and 11,000 captured. The Romans had only 100 dead.21

Concerning the battle of Pydna not much is known from our ancient sources but possibly things happened as follows. The strength of king Perseus' army is estimated at 20,000 phalangites, 17,000 other infantry, an elite agema of 3,000 men and 4,000 cavalry. On the other side, consul Lucius Aemilius Paulus had at his disposal a force of about 37,000 Romans, Italians, Pergamenes and Numidians plus 34 elephants. In June 168 BC the two armies were met at Pydna in southern Macedonia and the fighting began accidentally over a stream.

Initially, the charge of the phalanx was irresistible. The Macedonians advanced swiftly and after some fierce fighting the Romans made an orderly retreat towards rough ground. When the pursuing phalanx entered that area, it started to lose its cohesion and gaps were created in its long line. Realising this, Paulus ordered his legionaries to infiltrate in small groups wherever possible and fight many single combats at close quarters; thus, the phalanx gradually disintegrated. In the meantime, the Roman right had managed with a counter-attack supported by elephants to break the enemy left. On the other wing, Perseus with the main body of his cavalry had already fled. The remaining phalangites, being attacked now by all sides, were slaughtered; the 3,000 picked troops of the agema fell fighting to the last man. Within an hour everything was over. According to the sources the Macedonian losses were enormous, 20,000 killed and 11,000 captured. The Romans had only 100 dead.21 Last but not least, the issue of leadership. It appears that in this aspect too the Romans had an advantage. Philip, although he had realized that neither the place nor the time were suitable, finally made the fatal mistake to engage with only part of his force at Cynoscephalae in order to support his skirmishers28 Furthermore, the phalangites on the left flank tried to catch up with the rest of the charging army 'having no one to give them orders'.29 This incident clearly indicates a break in the Macedonian chain of command. On the other hand, with the 'brilliant initiative of the military tribune' who hit the phalanx at the rear the Romans won a total victory.30 Finally, Perseus seems to have lost control of his army at Pydna and fled early in the battle; his overall performance was lamentable compared to the competence and bravery displayed by Aemilius Paulus.31

Last but not least, the issue of leadership. It appears that in this aspect too the Romans had an advantage. Philip, although he had realized that neither the place nor the time were suitable, finally made the fatal mistake to engage with only part of his force at Cynoscephalae in order to support his skirmishers28 Furthermore, the phalangites on the left flank tried to catch up with the rest of the charging army 'having no one to give them orders'.29 This incident clearly indicates a break in the Macedonian chain of command. On the other hand, with the 'brilliant initiative of the military tribune' who hit the phalanx at the rear the Romans won a total victory.30 Finally, Perseus seems to have lost control of his army at Pydna and fled early in the battle; his overall performance was lamentable compared to the competence and bravery displayed by Aemilius Paulus.31