The catacombs of St. Callistus and St. Sebastian evolved through several stages of use after their inception in the early- to mid-third century CE. The architectural and inscriptional evidence offers us rich and varied testimony to the development of these sites from marginalized burial places for Christians under persecution to social and ecclesiastical centers for the cult of the martyrs during the fourth and fifth centuries. The development of the catacombs into cultic centers is reflected vividly in their architectural adaptation. Here, I will describe this architectural adaptation in terms of the social context of patronage in late antiquity.

Social Models of Patronage in Late AntiquityFirst, it is necessary to say something about the cult of the martyrs and the phenomenon of patronage during the late Roman Empire. In the early church, the "cult of the martyrs" was actually a set of social practices - including pilgrimage and the veneration of relics - connected to the remembrance of those who had died for their faith during times of persecution. As the cult of the martyrs developed, it drew criticism from certain church leaders who viewed it as a haven for "pagan" superstitions. Peter Brown (1981: 33) recognizes such criticisms largely as rhetoric designed to reassert the authority of the church leaders themselves, and argues that a "conflict between rival systems of patronage" actually lay at the root of this criticism. Patronage - the act providing financial support or protection in exchange for loyalty and services rendered - was a keystone of ancient social and economic relations.

Brown (1981: 34-36) sees the controversy surrounding the widespread cult of the saints in the late fourth century CE as the result of a political struggle between rich families and bishops - between aristocratic attempts to "privatize" burial practice and episcopal attempts to maintain public control over burial and veneration. Interestingly, however, he depicts the situation at Rome as an exception to this pattern of political conflict. Using late-fourth and early-fifth century evidence, he argues that the development of the cult of the martyrs in Rome reflected a "silent and decisive diplomatic triumph" by the church leaders. In other locales, competing claims of patronage erupted into open conflict; but in Rome, these claims were effectively harmonized under the auspices of the bishop of Rome.

Brown's study is important for its recognition of the role that patronage played in the cult of the martyrs. However, I do want to raise a point of caution about his treatment of the evidence (or lack thereof, in the case of Rome). His theory of social conflict leads him to describe the situation at Rome in terms of a "silent" resolution of an equally silent conflict over patronage rights. Episcopal administration of burial/cultic sites in Rome indeed would have been consolidated early on. However, the social lines between church leaders and aristocratic lay members were not always marked as clearly as Brown suggests. At the start of the third century, "men of wealth and rank" like Callistus, a freedman and banker, could still quickly rise to episcopal leadership (Krautheimer 1986: 25). Callistus' rise to the head of the Roman church was enabled partly by his reputation as one who had been imprisoned for his faith under persecution. However, it also may have been facilitated by his later patronage of Roman burial sites and the cult of the martyrs. During the first decade of the third century, Callistus was placed in charge of "the cemetery," by Zephyrinus, bishop of Rome (Hippolytus of Rome, Refutation of All Heresies 9.7; Stevenson 1978: 11). A few years later, Callistus was chosen to succeed Zephyrinus as bishop. Thus, patronage was not simply a forum for conflict between rich laymen and the clergy, but it also could be a means by which such social divisions were bridged.

How did patronage of burial places and the cult of the martyrs enable social advancement? For an answer, one must study how patronage relationships functioned. Richard Saller reevaluates the linguistic terms applied to patronage relationships in the Roman Empire. Specifically, he compares two models of patronage: patron-client (patronus-cliens) and friend-friend (amicus-amicus). While the patron-client arrangement involved persons of different social status, the friend-friend model was predicated on reciprocity in social transactions (Saller 1982: 11).

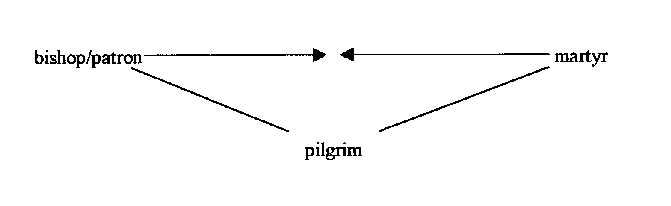

I suggest that both of these models pertained to the cult of the martyrs. The patron-client model operated on two different levels: 1) in the relationship between bishop or wealthy lay patron on the one hand, and pilgrim on the other, and 2) in the relationship between martyr and pilgrim. In each case, the patron is understood to confer benefits upon a dependent client. That client is expected to remain loyal to the church leaders and to the martyr. The following diagram illustrates these parallel patron-client relationships:

How does the friend-friend model of patronage come into play? Saller notes that the reciprocity enacted in such relationships often involved personal favors (officium-grata) extended to friends' clients and other friends (Saller 1982: 25). In this context, a mutual client could bring two patrons together into closer relationship. The following schema reflects the interplay of the two models in the context of the cult of the martyrs:

Thus, the patronage of the cult of martyrs by bishops and wealthy lay patrons effectively brought these figures into closer "friendship" (amicitia) with their fellow patrons, the martyrs. Furthermore, pilgrims, by their very participation in the cult of the martyrs, validated and enhanced the prestige of their ecclesiastical patrons. The sponsoring of architectural works for the cult of the martyrs was one way that church patrons laid claim to the authority of the martyrs. How then, does the archaeological evidence at Roman sites like St. Callistus and St. Sebastian reflect this work of patronage?

Architectural Adaptation in the Cult of the Martyrs: St. Callistus and St. SebastianThe catacombs attained quasi-official status as the burial site of the Roman church at least by first half of the third century. As I mentioned earlier, Callistus was placed in charge of "the cemetery" -- probably the site which would come to bear his name - by Zephyrinus early in the third century. The fact that Callistus was chosen to succeed Zephyrinus as bishop reflects the social significance of this burial site to the Roman church, as well as the early supervision of the plot by the episcopacy. Indeed, in the Crypt of the Popes within the Catacomb of St. Callistus one finds the burial place of the bishops of Rome from Pontian (d.235) to Miltiades (d.314). Only five bishops were not buried in the Crypt of the Popes during this period - three of them are found elsewhere within the St. Callistus complex: Cornelius (d.253) in the Crypt of Lucina, Gaius (d.296), and Eusebius (d.310). The Crypt of the Popes itself was formed from two chambers that predate 207 CE. By the year 250, they had been joined and decorated with two columns (Krautheimer 1986: 34, fig. 4; Mancinelli 1981: 21-22, fig. 40). In the context of the cemetery's connection with Bishop Callistus and the cluster of papal tombs, the formal architectural modifications to the Crypt of the Popes suggests a specific association with episcopal authority and patronage. The commemorative inscription of Pope Damasus (366-384) marks a culminative stage of oversight and organization by the bishopric.

|

The inscriptional and architectural evidence in the catacomb of St. Sebastian gives an even better sense of the rise of the cult of the martyrs and the role of patronage. The site at St. Sebastian is reputed to have been a temporary haven for the apostles' remains during the Decian persecution. Whether or not this reputation is legendary, the site's apostolic connection attracted many pilgrims. The numerous graffiti at the site invoking the aid of "Peter and Paul" or "Paul and Peter" attest to the rise of this cult of the apostles in the third century. Many these graffiti seem to have been hastily scrawled, as in case of a misspelled petition for the apostles to "pray for Victor" (Stevenson 1978: 31, fig. 18). Third-century architectural developments reflect formal episcopal patronage concurrent with the informal etchings of devout pilgrims.

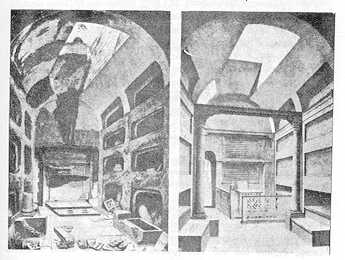

In the third century, the site was designed to accommodate festivals for the veneration of the martyrs: at that time, the martyr shrine consisted of an open courtyard, bordered on one side by "a funeral-banquet hall (triclia)" (Krautheimer 1986: 35, fig. 5). Most of the pilgrim graffiti is found on the surviving back wall of this triclia. A niche with a marble facing marks the cultic center, where pilgrims would have approached with their gifts and petitions. This structure dates from the inception of cultic festival in 258 CE - the date is confirmed by a petition to the apostles inscribed in 260 CE on the same wall. The construction of this courtyard and banquet hall reflects yet another stage of architectural development in the cult of the martyrs beyond the basic type of room enlargement that created the Crypt of the Popes in the Catacomb of St. Callistus mentioned above.

With the rapid growth of the cult of the saints in the late third and early fourth century, the needs of festival observance began to exceed the capacities of the early banquet hall at St. Sebastian. New architectural needs provided the opportunity for further ecclesiastic patronage. Inscriptional evidence attests the role of the Roman clergy in the authorization of excavations and building projects at the catacombs during this period. An early fourth-century inscription in St. Callistus reports:

The deacon Severus made a double chamber (cubiculum) with arched vaults (arcosolia) and a light well as a quiet resting place in peace for himself and his family by permission (iussu) of his pope Marcellinus.

Another inscription, found in the catacomb of St. Domitilla, points to the authority exerted by two presbyters around the turn of the fourth century:

Alexius and Capriola made [this tomb] in their own lifetime, by permission (iussu) of the presbyters Arcelaus and Dulcitius.

The term iussu in both cases reflects official language from the third and fourth centuries indicating permission of a superior authority (Stevenson 1978: 27).

In order to accommodate the larger number of pilgrims, a basilica was built on the site in the early fourth century. The plans and initial construction of this basilica may have begun just prior to Constantine's occupation of Rome in 312. The remains of a pre-Constantinian Christian hall are preserved beneath the later Baroque remodeling of the basilica. Such a hall (aula) would have represented a transitional stage between early funerary and later basilica architecture (Krautheimer 1986: 52-53).

|

The overlaying architectural layers prevent a thorough assessment of this hall-structure, but contemporaneous Roman parallels are suggestive. In the domestic realm, the hall-church of San Crisogone in Rome has attracted much attention as a similar stage of architectural transition: the adaptation of an early Christian meeting place away from the house church model. Another assembly hall construction may be observed as an intermediate stage in the architectural development of San Clemente (White 1990: 132-139). At San Clemente, the hall was adapted from rooms in a multi-story apartment building (insula). The funerary realm also provides an architectural analogy: the surviving remains of a building with three alcoves (cella trichora) above the catacomb of St. Callistus is an example of how more spacious martyr shrines and banqueting halls were built amidst open graveyards during this period (Krautheimer 1986: 35, fig. 7). Unlike at St. Sebastian, however, this earlier construction was never adapted into a basilica.

The basilica at St. Sebastian raises other issues important for tracing the growth of the martyr cult and the role of ecclesiastical patronage in facilitating that growth. The renaming of the original "Basilica of the Apostles" after St. Sebastian (martyred in Rome under Diocletian, ca. 303-305) probably reflected a lessening of apostolic veneration and a concurrent boom of local martyr reverence at the site. An inscription by bishop Damasus (d.384) provides possible evidence for this decline of apostolic veneration.

Whoever you are who seeks the names of Peter and Paul, you ought to know that here formerly the saints dwelt (hic habitasse [v.l. habitare] prius).

The word "dwelt" (habitasse) here probably refers to the apostles' temporary period of burial at St. Sebastian. Its reference to a past action may suggest that the cult of the apostles was already in decline when Damasus wrote. Indeed, while the hymn Apostolorum Passio (attributed to Ambrose, d. 397 CE) mentions the site as one of three Roman sites where the apostles were venerated, the Hymn of Prudentius (403 CE) does not mention the shrine at St. Sebastian (Stevenson 1978: 32-33). The decline of apostolic association with the basilica may have been in part the result of a shift in episcopal patronage. With the promotion of other sites more closely connected to the apostles' martyrdoms (e.g. the St. Peter's tomb at the Vatican), and with the rise of other martyr figures, the association of the basilica with the apostles Peter and Paul would have become less compelling.

The transfer of St. Sebastian's relics to the site that would henceforth bear his name especially indicates the underlying role of episcopal patronage. In late antiquity, the transfer of bodies and relics were often accompanied by large-scale architectural adaptation, as in the case of the Crypt of St. Cecilia in the catacomb of St. Callistus. There, an ossuary was built under the crypt for the relocation of numerous bodies - pilgrim itineraries mention anywhere from 80 to 800 saints buried at this site. A nearby plaque installed by bishop Damasus gives evidence of the official patronage that financed this project (Withrow 1895: 177-178). Similar acts of patronage would have funded the transfer of St. Sebastian's relics and the building of the martyr's basilica in the first decade of the fourth century.

Conclusion: Patronage and the Urban LandscapeFinally, patronage directed toward the cult of the martyrs also had a profound effect upon the urban landscape of Rome. The establishment of martyr shrines along the main roads outside the city walls effectively expanded the boundaries of the city (Brown 1981: 42). Referring to the cult of the saints and its effect, Jerome remarked that "the city has changed address" (movetur urbs sedibus suis; Jerome, Letter 107.1). The catacombs and the developing martyr shrines thus became a point of cultural contact between the urban residents of Rome and the populace in the countryside outside the city, a crossroad for the two-way flow of pilgrimage in and out of the city.

Some of these shrines came to function as the first "suburban" churches. The movement from periodic festival observance to more frequent, regularized community worship is difficult to trace. For instance, in the case of the Crypt of the Popes in the Catacomb of St. Callistus, an altar and chancel screens were installed in the early fourth century; yet it is unclear whether these additions were designed for an established, local parish community. They probably would have simply met the needs of pilgrim visitors. However, with the construction of larger churches such as the semi-subterranean Basilica of Nereus and Achilleus (in the Catacomb of St. Domitilla) and the Basilica of St. Sebastian, one can observe a definite movement toward providing facilities that would have accommodated more regular worship practices. These structures perhaps witness to the establishment of a resident community on the outskirts of the city alongside the ongoing practice of pilgrimage.

Thus, the promotion of these suburban martyr shrines ultimately led to a geographical reconfiguration of the Roman city. The construction of basilicas in cemeteries and martyr shrines outside the city walls represented a topographical shift, a reallocation of resources away from the traditional centers of Roman social power. In this way, ecclesiastical patronage of the cult of the martyrs helped reshape the geo-political landscape of late antique Rome.

Select Bibliography