|  |

ABSTRACT

The Bible Lands Museum, Jerusalem, Israel marks the turn of the new millenium with its special exhibition, "Images of Inspiration: The Old Testament in Early Christian Art". The xhibition examines the use of Biblical imagery in the art of the first Christians and reveals how the Old Testament provided an important source of inspiration for artists and artisans in Early Christianity. The exhibition traces the history of early Christian art.

|  |

INTRODUCTION

Throughout history man has expressed himself through art. Art is a

powerful language to convey beliefs, hopes and to reflect the history

of the people. Our heritage is carved in stone, painted in illumi-

nated manuscripts, set in mosaics, sculpted from clay or wood and

woven into textile for the perpetuity of mankind.

The same is true with the advent of Christianity. The early development of Christianity two thousand years ago marked the growth of a new religion whose roots had been deeply laid in Jewish soil. The first Christians were for the most part Jews, well-versed in the Old Testament, who regarded Jesus as the fulfillment of Biblical prophecies regarding the arrival of the Messiah. With this belief in mind, early Christianity interpreted the stories of the Old Testament, applying new layers of meaning to the traditional Biblical tales.

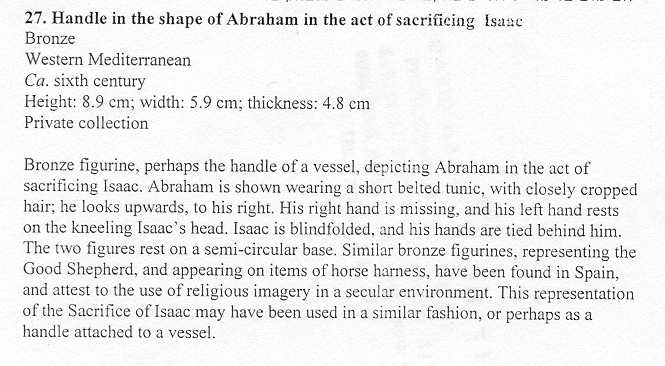

For example, the Biblical narrative of the Sacrifice of Isaac describes how God tests Abraham's faith by demanding his son Isaac as a sacrifice. In Jewish thought Abraham and Isaac become the supreme example of self-sacrifice in obedience to God's will and the symbol of Jewish martrydom throughout the ages.

Early Christians also saw the Sacrifice of Isaac as one of the most important Biblical stories, relating it to the actual sacrifice of another son, Jesus. For Christians, the depiction of Isaac's sacrifice in art, particularly in funerary art, came to be an allegory for the sacrifice of Jesus.

On the other hand, the story of Jonah is a story of redemption. The story tells of the redemption of Jonah from the large fish, the redemption of the people of the people of Nineveh, and the ultimate redemption of Jonah from the anger of God. The story of Jonah has come to be seen by Christians as a precusor to the life, death and resur- rection of Jesus, and their artistic images clearly defines it, "and in the same way the Son of Man will be three days and three nights in the bowels of the earth." (Mat 12:40)

|  |

THE BEGINNINGS

Next to nothing is know about the beginnings of a specifically Chris-

tian form of art; the first examples only appear about c.180 AD.

Various reasons have given by scholars, but the most commonly cited

factor is the aversion to representational arts rooted in the Jewish

origin of Christianity, "You shall not make carved images of your-

self..." (Exod 20-4).

As a child of Judaism, primitive Christianity was a religion simultaneously adverse to pictures in theory and opposed to their use in practice. This point of view was expressed by Christian clerics well into the fourth century and even longer in some places. They feared that having an image of the thing before you, vision and devo-\b tion might attach themselves to the image, and fail to press on to the thing of which the image stands. This viewpoint was maintained by the image-rejection iconoclasts of the Christian Church for hundreds of years with fluctuating success.

EARLY CHRISTIAN ART

By the late second and early third centuries, this attitude had

been changed and the Christian community began to use various art

forms to express the message of the new religion. The Christian

artist faced the problem of finding ways in expressing God's mysteries

adequately. The artist had to considerate the very foundations of

Christianity which are the doctrines of creation and incarnation. It

was inevitable that the early Christian artist should celebrate human

flesh, depicted in the image of God, made in the image of the incar-

nate god, and redeemed for the vision of god at last.

|  |

For the artist there was an enormously wide range of expressions that needed to be included in Christian art. This results from the central paradoxes of the Christian faith. They include paradoxes that arise when human imagination tries to function on the frontier that runs between time and eternity, between the transcendent and the imminent, or between the spiritual and the material.

For example, in depicting the Annunciation, an artist, in the patronage of the church, would try to catch the whole idea of our mortal flesh being hailed by God's splendor: He would depict the Virgin (our flesh) crowned with gold (raised to glory by the promise of redemption), sitting under gilded arches, being approached by a shining winged creature.

Another artist would show the Virgin as a very ordinary young woman, in ordinary surroundings. It was method of the popular artists of that era and their lower-class patrons who used the stories of deliverence, redemption and salvation taken from the Hebrew Scriptures, and healing and identity taken from the early Christian traditions.

The differences between the two ideas of painting in the artist's doctrines, are contrasting ways of coming to the subject. The Christian artist had to ask whether he had to paint 'religious sub- jects' (annunciation, nativitities, crucifixion, and saints' lives), or to show ordinary human life, relying on the symbolic themes to heighten the drama and to stress the religious significance.

Both trends may reflect the effort to present God's works and deeds to impress the gentile world. The pictorial representation of Christian themes was justified with the dictum, "Quod legentibus scriptura, hoc idiotis pictura." - 'As writing is to those who can read, so is painting to the ignorant.'

Christian art from the early centuries up to Renaissance tended to choose the first option of interpreting religious doctrines in their art. However medieval artists, far from ignoring ordinary life, brought the whole of everyday life into service. By the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the artists were depicting plain domestic, communal and professional life to convey the message of Christianity. Artists such as Titan, Rembrandt, Vermeer, van Rysdael and Cuyp are prime examples.

|  |

MEDIA OF EARLY CHRISTIAN ART

Early depictions of Biblical stories and images appeared on various

objects - illuminated manuscripts, frescoes, mosaics, sarcophagi,

textiles, vessels, coins, jewelery, gold decorated glass, carved

ivories, medalions, and household utensils. Early Christian art was as

diverse as the religions and sources from which it derived. Without

any overt Christian style or symbols, it is difficult to decide

whether an artistic object bearing an Old Testament narrative subject

to be assigned to Early Christianity or Jewish art. Consequently, it

is usually the context of the find that determines the attribution.

Thus, early Christian Art, usuallly refers to any work produced by or

for Christians.

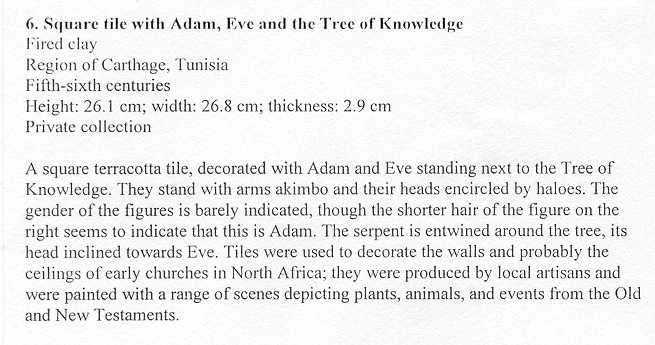

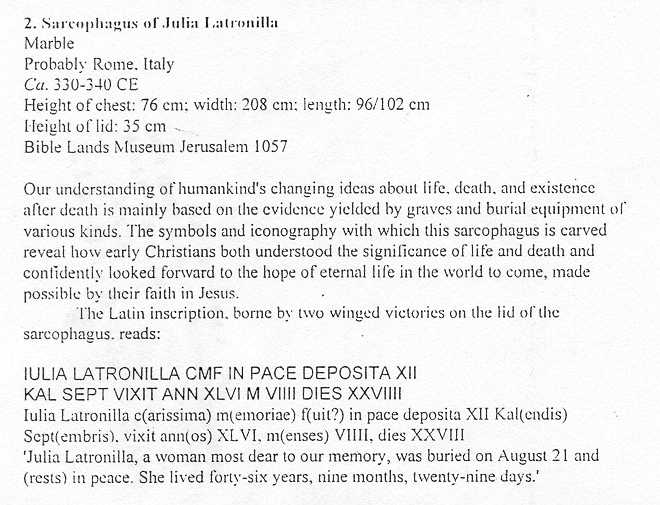

For example - A Byzantine clay lamp with Greek inscription (c. 6th-8th centuries) can be interpreted as "Light of Jesus. Light of Jesus." This inscription is clearly inspired by Psalm 27;1, although Jesus replaces Lord. The inscription is a good illustration of how the early Christians adopted and used the Hebrew Psalms.

Grape imagery appears frequently throughout the Bible. Isaiah likens God to the owner of a vineyard and Israel to the vineyard (Isaiah 5). Jesus is quoted as comparing himself to a viner: "I am the true vine and my Father is the vine-dresser." (John 15:1). Thus we see many Christian crafted artifacts with the grape imagery - pottery, amulets, oil lamps, medallions, etc.. Thus transferring the symbol from Jewish tradition to Christian symbolism.

Another interesting imagery adopted by the Christians was the 'Good Shepherd' symbol, "And the Lord said to you: 'You shall shepherd My people Israel; you shall be ruler of Israel'." (II Samuel 5:2). The allegorical figure of Jesus as the 'Good Shepherd' appears early in Christian literature (John 10:1-16 and Luke 15:3-7) and was elaborated by the early Church fathers, such as Clemens of Alexandia. Thus the image was easily assimilated to the Biblically-derived metaphor as describing Jesus. On the Early Christian art of late antiquity, the Good Shepherd had a clear significance as a philantropic saviour.

The earliest example of the adoption by the Christians of the 'Good Shepherd' motif seems to be the third-century clay lamps produced by Annius Serapidorus, a potter specializing in producing lamps bearing this motif. In Rome the Good Shepherd appears in funerary contexts late in the third century. The motif occurs in the mosaics of the cemetery under St. Peter's, in the wall paintings of the Tomb of Aureli, and in the Catacombs of Via Latina of Domitilla, and of Callistus. The popularity of this motif continued after the reign of Constantine (c.306-337 AD), when Christianity became the official faith of the imperial court. It became depicted on statuary, wood panels, slip-ware plates, gold decorated rings. etc...

|  |

CONCLUSION

The Early Christian era begins with recognition of Christianity at the

official religion of the Byzantine state (c.313 AD) or with the

foundation of its capital Constantinople (c.330 AD) and closes with

reign of Justinian (c.565 AD) or, according to scholars, with the

reign of Herakleios (c.630 AD). During this period the tradition of a

grandiose imperial art based on the Roman character remained vigourous

and unbroken.

The beginning of Iconoclast period (c.725-843 AD) is one of extreme importance, for it witnessed the destruction of many works of arts, and the development of representational art was arrested as a result of the official attitude regarding the proscription of icon-worship. Religious painting consequently acquired a purely secular or decorative character. Only after the Iconoclast period (c.725-843 AD) Christian religious painting assumed a definite form, always of high artistic quality and of outstanding technical perfection, coexisting in a single dramatic art.

Consequently, Christian representational art became fixed, and the Biblical repertoire was greatly encriched. Theological intrepretations also premeated early Christian art, both because of Christian reinter- pretations of the Old Testament and because of Christian interest in establishing the continuity of the Old and New Testaments. Even when divorced from the Book, Early Christian illustrations generally retained the close relationship to the Biblical text, with the addition of borrowed elements from extra-Biblical sources introduced to heighten the drama and to stress religious significance.

REFERENCE1) Catalogue 'Images of Inspiration' - the Old Testament in Early Christian art, edited by Joan Goodnick Westenholz, curator, Bible Lands Museum, Jerusalem. 2)Christianity and the Arts - Thomas Howard, Lion Publishing, USA. 3)The Arts of Man - Eric Newton, Thames and Hudson, London. 4)The Byzantine Museum, Ekdotike Athenon SA., Athens. 5)The New English Bible, Oxford University Press, Cambridge.