|

|

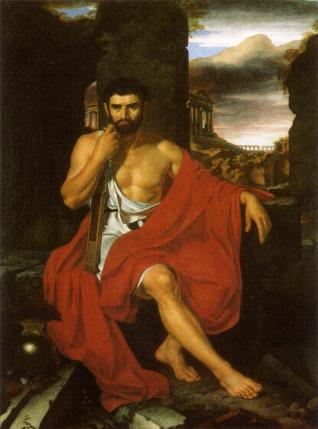

The painting is Caius Marius Amid the Ruins of Carthage completed by John Vanderlyn in 1807, and can be found at the MH DeYoung Museum in San Francisco, Gallery 18. In this neo-classic historical painting of the Roman Marius, he sits in the foreground of the painting staring out from the ruins of Carthage. Vanderlyn derived this subject from Roman texts, collections and the study of the great masters.

Marius' posture creates a stable pyramid composition from his head, to the extension of his arms that take you to the immediate foreground of the painting. The light source comes from the viewers' space, as you can see from the shadows that fall on the monolithic blocks in the foreground. With excellent attention to detail, Vanderlyn has also included a reflection of light on the helmet, also in the foreground, that tells us exactly where the light source is. By using a light source from the viewer's space Vanderlyn allows the viewer to enter the scene.

Vanderlyn used linear perspective, putting the vanishing point behind Marius' head in the distant ruins of Carthage. In this distance we see what must be part of Carthage, standing in ruin and becoming overgrown with vegetation. As far in the distance as the ruins are, you would expect them to be a little hazier. There is a very small use of sfumato; Vanderlyn was probably eager to display his talents in portraying Roman architecture and discarded sfumato for that purpose. Neo-classical artists strove to duplicate the architecture of the Greek and Roman eras, and Vanderlyn has certainly done so in this portrait. Also, Vanderlyn minimizes the buildings to allow Marius to be the focus of the painting. The sky is cloudy and foreboding, lending to the largely ominous presence of Marius.

Marius is partially draped in a red cloak beautifully rendered with great attention to the natural appearance of the folds, and the shaping of the body beneath the cloak. Through a gradation of value in the red hue, the folds of the red cloak are created, and there is a tactile quality to it that sets off against Marius' flesh and clothing. Red is a powerful color, but Vanderlyn has given it a rather serene quality through his subtle use of light and shadow.

The red cloak adds an interesting twist to the picture. The cloak entirely covers Marius' left leg, leaving only his left foot and right leg in the painting. Marius had tumors that covered both legs and decided to have the tumors removed since he disliked the deformity. Without being tied up or drugged, the tumors were removed from one leg. Marius decided that the effect was not worth the pain and declined to have the tumors removed from the other leg (Plutarch). Perhaps knowing of Marius' surgery Vanderlyn opted to cover the leg that still had tumors.

Marius' clothing is torn on his left side, revealing a vital chest that holds a minute red reflection from his cloak. The torn cloth hangs to the right, and Vanderlyn has used a subtle contrast of light and shadow to suggest the natural folds of the drapery. Vanderlyn also uses light and shadow to create the powerful appearance of Marius' muscular physique. The more subtle shadows play across the muscles, lending to the very powerful and taut appearance of the muscles. Part of his chest is thrown into a very dark shadow by Marius' chin and the sheath in his right hand.

Marius' youthful body is idealized and in sharp contrast to the story shown on his face. In this way, Vanderlyn expresses the individualization of ideal form that was a tenet of Neo-Classicism in art.

Marius' face is worn with the wrinkles that develop over time; the large bags beneath his eyes and sagging cheeks are signs of his age. These sagging cheeks, hidden almost completely in a beard, take us to Marius' mouth set in a frown that seems permanent. Marius' neck muscles are taut and his eyebrows are knit; he is focused on the far distance. His hair is tousled and unkempt, and his clothes are in a state of disarray; he has neglected his personal appearance. However, while his clothing is disheveled, Marius' prideful look prevents him from appearing slovenly.

He stares out into the distance morosely ignoring his own surroundings and looking over the head of the viewer. He sits frontally, and his present state of mind comes through; he conveys pride, discipline, security and a sense of deep concentration. Simultaneously, he imparts a feeling of regret, loss, isolation, and determination in the face of his present situation. Marius sits with a rigid back, but his self-assuredness lends to a look of relaxation. His left arm, covered from the shoulder to the wrist in the red cloak, rests casually on a block of stone that lies next to his torso. The left hand rests casually off of the edge of the block and is partially in shadow as there is little light on the left side of Marius. This hand leads you to his right foot, extended into the immediate foreground.

This perfectly proportioned foot leads you up his powerful right leg and back to the right side of Marius. In his right hand Marius holds fast to his sheathed sword which is parallel to his torso. His right hand wraps around the top of the sheath, and Vanderlyn has done a wonderful job of defining the tendons and knuckles in that hand. Because of the appearance of the tendons on the back of Marius' hand, an impression that Marius is both clutching and leaning on the sheath is created.

Vanderlyn was an American painter who might have been successful in France had he truly pursued fame there. Ironically, he presents Marius in a situation that was similar to Vanderlyn's own situation in America later in his life. After his return to America in 1815, Vanderlyn experienced rejection from his American peers. His American showing of "Adriane on the Island of Naxos" in 1816 wherein Adriane is nude, he received not praise for his artistic talent but a reaction of shock from the American public. They had become too prudish to appreciate Vanderlyn's portrayal of Adriane. However, when Caius Marius was completed, Vanderlyn had not yet experienced his greatest disappointments in America. In fact, he received a gold medal from Napoleon for "Caius Marius" in 1808.

Marius, having been exiled from Rome seeks the favor of Sextilius, a Roman governor in Africa. A message is conveyed to Marius' ship as it reaches port in Africa; Marius will be treated as an enemy of Rome should he set foot on African soil. To this Marius replies, "Go tell him that you have seen Caius Marius sitting in exile among the ruins of Carthage." (Plutarch's Liver) In this way Marius compares his fate to that of Carthage, a once powerful city now sitting as a deserted ruin. The dejection of Marius is conveyed with mastery. His life story is one of constantly unsatisfied ambition that ended in fear and shame.

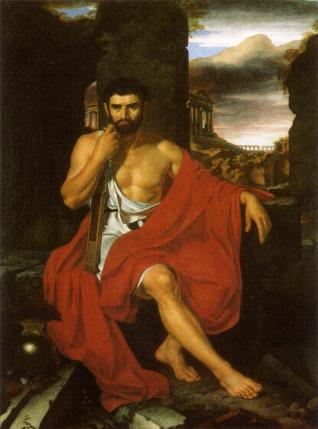

Vanderlyn was greatly influenced by the artist Jacques-Louis David, who was a prominent painter in the Neo-Classical style and was the official painter for Napoleon. The portrait of Napeleon in His Study, by David, strays from the idealized style of Neo-Classicism.

|

Napoleon is shown in his study in a rather complicated posture. This posture subtly idealizes his body by not allowing us to see Napoleon's girth. David isn't blatantly hiding any physical shortcomings of Napoleon's; he plainly shows Napoleon's portly abdomen and thinning hair. Rather than diminishing the stature of Napoleon this effect humanizes him. This approach is much different from Vanderlyn, who has clearly idealized the physical appearance of Marius to add to his presence in the painting.

David has illuminated Napoleon with a light source within the picture plane. Using the light source from within the painting retracts from the humanization of Napoleon, and places him back in a realm that the viewer cannot be a part of. Vanderlyn chose to invite the viewer into Marius' space to allow the viewer to be share of Marius' emotional state.

The background in David's Napoleon is not as devised as the background of Caius Marius. David has included hazy objects with light colors in the background to focus your attention to the more colorful foreground. In Caius Marius, Vanderlyn does not create that much difference in color in the background; instead he diminishes the background.

Napoleon stands above the viewer, and like Marius, focuses his attention on the distance. There is a marked difference between their gazes; Napoleon looks pleased, friendly and confident about the future whereas Marius looks dejected.

|

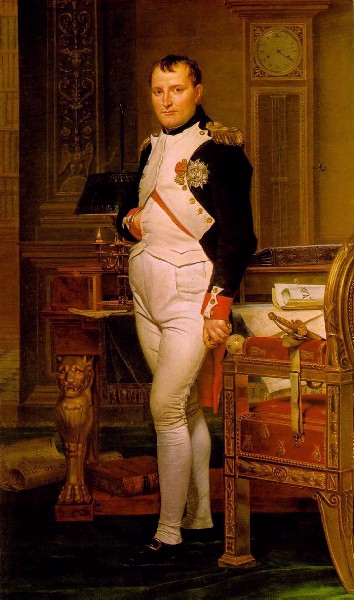

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, considered a Romantic painter, portrays Napoleon on his coronation day in the painting titled Napoleon on his Imperial Throne. Ingres has placed Napoleon in a full frontal sitting posture on his throne against a neutral background and creates a symmetrical composition with the two staffs that Napoleon holds. This symmetrical appearance is emphasized further with the organized looks of the folds of Napoleon's cape. Napoleon gazes down at the viewer, and you sense that he is aloof; there is not the emotion that is portrayed in Marius or David's Napoleon. As in the portrait by David, the light source comes from within the picture plane and prevents the viewer from being part of the scene. He shares the same posture as Phidian's colossal statue of Zeus that once stood in the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. This connection to Zeus is solidified by the appearance of the eagle on the rug in the foreground.

Ingres' Napoleon wears a beautiful red cape that echoes Marius' red cloak. Napoleon's cape appears to be extremely soft and is much more voluminous than Marius' cloak. Ingres uses very stark and subtle contrasts to create the volume of Napoleon's cape whose folds appear to be more contrived than those of Marius' cloak.

All three of these paintings portray great leaders in different ways and each capture a sense of the spirit. The two portraits of Napoleon glorify a living man, while Marius edifies in the spirit of Neo-Classicism.

The portrait of Marius, although not of a living person is much more personal. From that portrait there is a deeper understanding of the torture of Marius' soul; he warns us to appreciate what we have and not to let our personal ambitions destroy our lives as he did. Vanderlyn, in personalizing Caius Marius so well, truly stands out as an exceptional portraitist.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION