Issue P031 of 3 March 2003

The Romanization of Britain

The Role of Villa Owners in the Romanization of the Native Religion in Britain

Chedworth Roman Villa

by

Geoff Adams

Ph.D cand. (Hist/Arch)

The University of Adelaide, Australia

There are several aspects to be discussed throughout this investigation, but the central focus will be the native aristocracy and their response to Rome. This, it is believed, will reveal that the Romanized buildings erected by the native nobility have created an appearance of Romanization, with little significance for the nature of society in Britain as a whole. To support this hypothesis, it will be helpful to consider the elements of this apparent Romanization, namely the archaeological evidence for rural Romano-Celtic temples and Romanized villas in Britain. The structures at Chedworth in Gloucestershire have been used as a case study to allow a thorough examination.1 Temples of the 'Romano-Celtic' style were one of the features of the landscape in Britain during the Roman occupation, but it will be argued that the continuation of these temples has produced a false representation of the religion and the Romanization of the period.2 They were simply a representation of the Romanized attitude of the native aristocracy. In view of the fact that this group comprised only a very small percentage of the overall population,3 this ready adoption of Roman architectural methods is a poor representation of the beliefs of the entire rural community. An attempt will be made, therefore, to determine the extent of the social and religious impact of Rome on the native population, and on those who accepted Roman beliefs.

One of the most prominent features of Romanization in the British countryside during the occupation were the Romanized villas, symbolizing the benefits of adopting classical lifestyles. Most of these structures represent the native aristocracy's desire to exhibit and maintain their status and prestige through the construction of houses with Roman-style architecture and materials.4 The construction of Romano-Celtic temples was probably an extension of this pro-Roman attitude: structures erected by the aristocracy to emphasize their growing romanitas. Therefore, if a connection between these Romanized buildings can be proven, then it would also illustrate the small percentage of the population which these structures represent.5

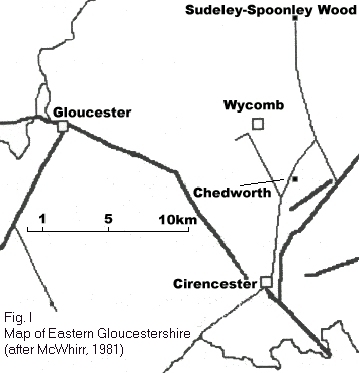

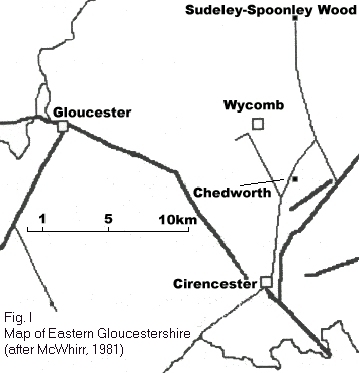

One of the wealthiest villas in Gloucestershire which does show the distinction between different groups of residents can be found at Chedworth (Fig. I). This villa (SP 052134), one of the most famous Roman sites in Britain, clearly reflects the desire of the native aristocracy for status. The reason for the location of the villa was probably the availability of water, as there was a natural spring in the north-west corner of the complex.6 The original unpretentious villa was established in the early/mid-second century (Fig. II).7 It began as three separate buildings on three sides of a courtyard and was gradually connected.8 The addition of luxurious facilities and the majority of the improvements to the villa occurred early in the fourth century AD.9 The building may have been originally built with timber in the form which it later took in stone, representing a gradual process of Romanization from form to material adaptation. Later in the century, after a destructive fire, it was replaced in an extended form with baths and more rooms (Fig. III). Features included a wealth of decorated walls, stone sculptures, mosaic floors, comfortable heated rooms and bathing facilities.10 These changes reflect the high degree of wealth of the dominant resident, as such additions were notably absent from other sections of the villa.

One of the wealthiest villas in Gloucestershire which does show the distinction between different groups of residents can be found at Chedworth (Fig. I). This villa (SP 052134), one of the most famous Roman sites in Britain, clearly reflects the desire of the native aristocracy for status. The reason for the location of the villa was probably the availability of water, as there was a natural spring in the north-west corner of the complex.6 The original unpretentious villa was established in the early/mid-second century (Fig. II).7 It began as three separate buildings on three sides of a courtyard and was gradually connected.8 The addition of luxurious facilities and the majority of the improvements to the villa occurred early in the fourth century AD.9 The building may have been originally built with timber in the form which it later took in stone, representing a gradual process of Romanization from form to material adaptation. Later in the century, after a destructive fire, it was replaced in an extended form with baths and more rooms (Fig. III). Features included a wealth of decorated walls, stone sculptures, mosaic floors, comfortable heated rooms and bathing facilities.10 These changes reflect the high degree of wealth of the dominant resident, as such additions were notably absent from other sections of the villa.

The social differentiation within the Chedworth villa was shown by the internal layout, with the wealthiest accommodation being in the western wing of the villa. This wing was entered from the courtyard through a porticus which led into a shrine room with smaller domestic rooms beside it. The northern wing did not have the same level of facilities as the western side, and the southern and eastern wings were still less well served, not sufficiently important to be entered from the courtyard. No doubt the western wing would have conveyed the impression of a successful villa owner, with amenities which accompanied such success. In one of the rooms (Room III) in the southern wing, a large number of coins were discovered, suggesting that it was used for the issuing of payments.11 If the positioning and the proximity of this room to the higher status western wing are taken into account, it seems quite appropriate for a function of this kind.

A Romano-Celtic temple has also been discovered at Chedworth (Fig. IV). This temple is located around 800 meters south-east of the villa complex, on a hillside near the Coln River. The temple was roughly square in shape, with a portico of 15.5 meters by 15 meters.12 A pit, probably votive in function, was discovered within the ambulatory of the temple,13 producing human remains and the bones of a red deer.

The use of pits for votive dedications during the Iron Age in Britain is well attested,14 and such a dedication at this Romano-Celtic temple suggests that the sanctity of the site predates the building. Further evidence for the continuity of sanctity was a stone relief of a hunter with a dog and stag, which was one of the most notable finds from the site.15 There may well have been a native hunting deity connected with the shrine, for example Silvanus, but the proximity to the Coln River may also indicate a water cult.16 The temple itself has been dated to the mid-second century AD, and it probably continued in use until some time during the fourth century. Massive, well-finished blocks, some as large as 1000 by 600 millimeters, were used for the construction of the podium. This was a temple of some pretensions, possibly erected by an aristocrat seeking to impress visitors to the site. In further support of this suggestion, the temple at Chedworth has also produced evidence of masonry capitals, which were exceedingly rare in Roman Britain.17

The relationship between these structures could lead to the assumption that both the temple and villa were constructed by the dominus of the villa to emphasize his prominence within the surrounding rural community. The building of Romano-Celtic temples in rural areas was not necessarily expected, but there is little doubt that, in general, any prosperous villa owner could have erected such a temple if he chose;18 it is assumed that the erection of the wealthiest villas was undertaken only by those who sought to elevate themselves socially because of their greater resources. To build significant villas and temples was an expression of power, intended to impress not only the local population, but also visitors and others,19 such as the Roman administration.

At this point it is important to clarify the methods by which an association between these structures can be proven. It may be possible to demonstrate a connection between Romano-Celtic temples and villas by examining the architectural materials and styles. The ground plans of these two types of structures were obviously quite different, but there were still elements which may provide a link. This analysis is based on the premise that the similar attributes found in two sites may provide an indication of a close connection, in preference to those with more dissimilar characteristics.20 These common finds suggest a level of interaction that reflects the presence of a transport and material connection between the sites.21 One example of this could be the common use of columns, which were a rarity in Roman Britain. Another link could be the common use of decorative styles and themes. The wealth invested in these structures may also provide another indication of an association.

Another method of defining an association between villa complexes and temples is through dating and chronology. It stands to reason that, in the rural areas, the majority of villa owners would have erected their Romanized residences before any masonry temples and shrines. This was different from the urban centers where many of the stone public buildings were built before the domestic housing because, a result of the native leaders' seeking an elevation in the status of the town. The simultaneous construction of a temple and villa would have meant a great deal of expense for a villa owner, and would only occur rarely. While the dating of the evidence is problematic because it is not usually very precise, the use of chronological evidence may add further weight to a plausible association between some villas and temples. It is through a combination of these methods a connection may be established.

These methods should now be applied to try and prove an association between the Romano-Celtic temple and Romanized villa at Chedworth. As mentioned previously, the Romano-Celtic temple at Chedworth was located only around 800 meters to the south-east of the villa.22 The proximity of the two buildings suggests an association between them. There is evidence of Iron Age sanctity at the temple complex and the continued use of the site suggests some persistence of native beliefs. This is shown through the use of a votive pit for depositing dedications within the structure; during the Iron Age the use of such pits for ritual purposes was quite common.23

The masonry temple building was probably built during the mid-second century AD.24 The date corresponds well with the time of construction of the first masonry phase of the southern wing of the villa complex (Fig. II).25 The early phase of habitation at the villa had already occurred by the middle of the second century, and it is probable that the Romano-Celtic temple had been constructed shortly this. A difficulty arises, however, when the well appointed Romano-Celtic temple is compared with the relatively modest villa of the second and early third century. The basis for this apparent dilemma is the discovery at the temple of sculptured masonry, such as Tuscan capitals,26 which indicate the lengths to which the builder went to decorate the temple. These architectural pieces seem to reflect the later wealth of the Chedworth villa, corresponding well with its luxurious development during the early fourth century.27 The remaining evidence for the temple is quite limited, mostly owing to modern disturbance, so it is impossible to ascertain a reliable sequence of development at the site. But it appears that, in all likelihood, there was more than one phase of development for the temple, and these pieces of ornate masonry may well reflect a later addition to it.

To further this suggestion, there seems to have been some architectural similarities between the two sites, which provide some additional evidence for an association. During the later phase of the villa, small columns were used in the western and southern wings to add support for the roof.28 These "dwarf" columns were positioned on the veranda of these two wings and reflect the wealth of the villa dominus.29 In view of the relative rarity of columns as an architectural feature in Roman Britain,30 their discovery at both of these complexes may be significant in further showing an association between them.

It seems very probable that there was an association between the Chedworth Roman villa and the Romano-Celtic temple, not only because of the relative proximity of the complexes and the close date of foundation for both sites, but also the architectural similarities. The temple would probably have been used by the native population and not only, in this case, by the villa owner himself, in view of the household shrines located at the villa site for private religious observances. The erection of this temple structure was probably meant to allow the villa owner to appear more Romanized and to advertise his social, financial and possibly political status and success. Owing to the continuity of sanctity at the site, it is unlikely that the rituals and beliefs centered there would have changed, with the majority of the population continuing to revere the local deities. Even just in Gloucestershire there are several other examples of villas and Romano-Celtic temples which seem to display a close connection. A few examples are the temple at Lydney Park and the Chesters Villa, the Uley Romano-Celtic temple and the Frocester Court villa, and also the complexes at Claydon Pike. All of these sites have displayed similar connections, but for the purpose of this study the focus should remain upon Chedworth.

To gain a better view of the religious persuasions of the Chedworth villa inhabitants it is pertinent to examine the domestic religious activity at the complex. The household shrines of the Roman villas provides a valuable insight not only into the religious focus of the inhabitants, but also into the social climate and structures within the villa community itself.31 Such shrines were commonly erected in a position where they connected buildings or farmyards and must have had a unifying function for the households in the extended villa group. This function can be illustrated by their common central positioning within the main residential building, near the entrance, or between the individual households. The location of the shrine might also indicate the differing social positions of the inhabitants of the villa complex itself.

The literary sources provide numerous accounts of the importance of household shrines in Roman daily life. In his De Legibus, Cicero refers to their importance and the necessity to observe the correct rituals: Ad divos adeunto caste, pietatem adhibento, opes amouento. qui secus faxit, deus ipse uindex erit......In urbibus delubra habento; lucos in agris habento et Larum sedes.32 Cicero also refers to the Lares in the De Re Publica, as an integral part of Roman life: Ad vitam autem usumque vivendi ea discripta ratio est iustis nuptiis, legitimis liberis, sanctis penatium deorum Larumque familiarium sedibus, ut omnes et communibus commodis et suis uterentur. nec bene vivi sine bona re publica posset nec esse quicquam civitate bene constituta beatius.33

Plautus, in the Aulularia, emphasises that the Lares were to be respected by the members of the household, especially by the paterfamilias: Atque ille vero minus minusque impendio curare minusque me impertire honoribus. item a me contra factum est, nam item obiit diem.34

Free-standing and detached shrines are easier to recognise than those incorporated within buildings because they are distinct from the main domestic structures. Quite often these shrines had classical features, including sculpture and inscriptions.35 Several contained water-cults, for example at Chedworth (Fig. II). Such structures would have also housed images of the domestic deities, and would have performed a similar social function to the internal household shrines.

At the Chedworth villa, the private shrine consisted of an apsidal building that was erected to the north-west over the spring which gathers near the villa.36 A large stone column was discovered in the octagonal basin and was probably one of a pair which stood at either side of the entrance to the sanctuary.37 The building was square in shape but with an apse at the back, and was obviously architecturally impressive. Reconstruction has shown that it would have stood roughly 2 meters high.38 The shrine would have existed, in one form or another, from the initial phase of the villa's development (Fig. II).39 The residential buildings in the courtyard were skewed in the direction of the shrine,40 which may indicate that the sanctity of the spring predated the erection of the villa, and even the shrine itself. In the north-eastern corner of the shrine was an uninscribed altar, which was most likely dedicated to a water-goddess.41 The discovery of this altar and its association with water has generally led to the identification of this shrine as a nymphaeum.

Several other small altars with pagan figures were found in association with the shrine. One of these was a representation of Lenus Mars.42 The stone bears a crudely-carved figure with a spear and an axe,43 the eyes, nipples, navel and genitalia indicated by sunken points which may have been colored. There was an inscription [L]en(o) M[arti] beneath the figure. Lenus was a Treveran deity that was associated with certain aspects of healing, but he was often artistically portrayed as a warrior44 Another altar was discovered with a similar figure, but highly-stylized, and this may have been to the same deity.45 The lines on the side of this particular altar are taken to represent circular shields and spears and reinforce the interpretation of the figure as a depiction of Mars. A small figurine of bronze has also been discovered in connection with the villa complex. It may represent a priest or the household's paterfamilias,46 adding further evidence for the classical emphasis of the religion of the inhabitants. It has been argued that the entire Chedworth villa complex was a religious center,47 but this appears to be unlikely, since there is no dominant central temple within the site.48

There were several other dedications from the later Roman period at the villa, including three inscribed slabs.49 These stones reveal that Christianity probably became the dominant belief.50 The slabs all bear the Christian chi-rho symbol and further demonstrate the continuing traditions of sanctity not only into the Roman period, but even into the Christian era. It may be that this represents the deliberate Christianizing of the stones around a former pagan shrine.

The villa at Chedworth had another shrine, a household-sanctuary, located within the main domestic building. The evidence for this shrine is mostly through the characteristic wide opening of the entrance and its central position between the separate household residences in the main wing.51 Small domestic rooms were located on either side of the room, serving the individual households within the building. This possible shrine-room was larger in size and would have provided a distinction between the different residential groups. It was obviously a central feature of the structure, being open to all visitors to the villa and also to the domestic quarters. The shrine was obviously of a later date than the nymphaeum, in use only after the main focus of the building was moved towards the center of the structure.52

This complex represents the highest social grouping within the community, those aristocrats who had sufficient funds to erect the most palatial residences. But one important factor that must be remembered is that these Romanized villas do not truly represent the people in rural Gloucestershire, the majority of whom continued to live in native-style housing during the Roman occupation. The architecture and materials used by the villa complexes was a clear expression of romanitas, which was also a notable aspect of the Romano-Celtic temples in the region.

In general, there seems to have been continuity of sanctity at many of the Romano-British religious sites, which usually occurred in the form of the erection of Romano-Celtic temples over Iron Age sacred places or shrines, such as at Chedworth. Another continuation of belief can be seen in the offering of Roman style altars and inscriptions in watery contexts. This is indicative of the cultural assimilation which occurred in Roman Britain where native beliefs and rituals continued within a Roman context. Despite the new building materials and appearance of the Romano-Celtic temples and the new forms of votive dedication, the local beliefs remained an integral part of the Romano-Celtic religion and should not viewed as secondary to the Roman pantheon. This is especially important when the influential role of the native aristocracy is taken into consideration. It was this group which actively sought to assimilate the two religious customs, and this is seen in the close association between many of the villas and the Romano-Celtic temples, including Chedworth.

The connection been these villa and religious structures has been shown using several types of archaeological evidence. The most important and obvious of these, in this instance, is the relative proximity of the two sites. Naturally, this distance alone cannot prove an association. Architectural similarities of structures were also used in order to suggest a connection between the villa and temple. This follows the basic premise that if the temple was to have been constructed by a villa owner, similar architectural techniques and styles may have been used at both sites. This has been shown explicitly at the temple and villa structures at Chedworth, through their use of decorative sculptural ornamentation.

In view of the close association between this villa and Romano-Celtic temple, there are some conclusions which can be drawn concerning the nature of Romano-British society in the region and the important role that the native nobility undertook in the assimilation of the two religions. Despite the prominent part played by the British aristocracy it would seem that the Romanization of the native religion was not as far reaching as it might appear. Most of the rural population seems to have persevered with their native religious traditions without any serious change. The continued use of Iron Age sanctuaries may indicate that there was little alteration to their beliefs. The limited nature of this religious assimilation seems to have also been the case in Gaul, where continuity of sanctity at many pre-Roman sacred sites has also been noted into the Roman period, under the guise of Romano-Gallic religion.53 Derks has argued that, in Gaul, the local communities maintained the essence of their own traditions, despite the introduction of elements of Roman culture. This is not to say that, in either Britain or Gaul, there were members of the Romano-British society who did adopt Classical deities, but, again, this would have been predominantly from the local nobility. Indeed, the adoption of Classical religion by some of the native aristocracy in Roman Gloucestershire has been evidenced in the some of the household shrines in the villa complexes.

Several of the villas in Gloucestershire contained household shrines. In the literary sources, the existence and importance of these domestic shrines has been mentioned frequently, and was a significant factor in Roman religion. Those members of the Romano-British society who had adopted Roman lifestyles and customs would, therefore, have seen these domestic rituals and the household shrines as an essential feature of both their public and private romanitas. These religious foci were varied in regard to their position within the settlement. There are a couple of examples of free-standing standing shrines in Gloucestershire, such as at Chedworth and Sudeley-Spoonley Wood. The shrine at Sudeley-Spoonley wood seems to have been dedicated to Jupiter.54 The detached shrine at Chedworth is quite different, probably having Iron Age origins. This shrine was a nyphaeum, housing a spring near the villa. There were quite a few water shrines associated with villas, such as at Great Witcombe and Frocester Court. Both Chedworth and Frocester Court seem also to have represented a continuation of Iron Age belief, with the residents beginning to deposit altars and inscriptions in the Roman custom after the erection of the villa. It appears, therefore, that in a few instances the native aristocrats who resided at these complexes assimilated their household rituals within a Roman framework, as they had done with the construction of the Romano-Celtic temples.

The influence which the native aristocracy had upon the Romanization process in Britain cannot be underestimated. It was through this group that the provincial administration was able to maintain the pax romana, because of the dependence of the poorer classes upon the local nobility.55 Rome maintained this aristocratic social order by offering incentives to the native leaders through the taxation system and also by the offer of citizenship for holding administrative and political offices.56 It would have been largely to retain their status that the nobility sought to construct Romanized villas, to build new temples on the site of their traditional sanctuaries and to adopt Roman lifestyles.57 The Romanization process can thus be clearly seen to benefit both the Roman administration and the local elites. But the majority of the population, being the rural lower classes, do not appear to have been a part of this assimilation process. Their daily lives would have probably changed very little, with most continuing to follow their traditional methods and customs. Their religious practices would not have alter drastically either, despite the introduction of a new architectural form for the shrine at the sacred places. The Romanized structure built by the leaders was of less importance than its location, and the genii loci had no real need for it.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Cicero, De Legibus, tr. Walker Keyes, C., Heinemann, London, 1948.

Cicero, De Re Publica, tr. Walker Keyes, C., Heinemann, London, 1948.

Plautus, Aulularia, tr. Nixon, P., Heinemann, London, 1928.

Secondary Sources

G. Adams, "Who built the rural Romano-Celtic Temples? Lydney and the Chesters Villa: a case study", Melbourne Historical Journal Special Issue: Proceedings of the Mass Historia Postgraduate Conference 2001, 2002, pp. 25-8.

Anon., 1889-90, "Chedworth Roman Villa", Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 14, pp. 214-15.

Blagg, T.F.C., 1980, "The Decorated Stonework of Roman Temples in Britain", in Rodwell, W. (ed.), Temples, Churches and Religion: Recent Research in Roman Britain, BAR, Oxford, pp. 31-44.

Clarke, S., 1996, "Acculturation and continuity: re-assessing the significance of Romanization in the hinterlands of Gloucester and Cirencester", in Webster, J. and Cooper, N.J. (eds.), Roman Imperialism: Post-Colonial Perspectives, Leicester Archaeology Monographs, Leicester, pp. 71-84.

Cunliffe, B., 1992, "Pits, Preconceptions and Propitiation in the British Iron Age", Oxford Journal of Archaeology 11, pp. 69-83.

Dark, K. and Dark, P., 1997, The Landscape of Roman Britain, Sutton, Stroud.

De la Bedoyere, G., 1993, Roman Villas and the Countryside, B.T. Batsford, London.

De la Bedoyere, G., 1999, The Golden Age of Roman Britain, Tempus, Stroud.

Derks, T., 1998, Gods, Temples and Ritual Practices, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam.

Esmonde Cleary, A.S., 1994, "Roman Britain in 1993: Sites Explored", Britannia 25, pp. 261-91.

Farrer, J., 1870, "Chedworth Roman Villa", Journal of the British Archaeological Association 26, pp. 251-2.

Fox, G.E., 1887, "The Roman Villa at Chedworth, Gloucestershire", Archaeological Journal 44, pp. 322-36.

Gatrell, A., 1983, Distance and Space: a geographical perspective, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Goodburn, R., 1983, The Roman Villa - Chedworth, National Trust, London.

Goodburn, R., 1998, Chedworth Roman Villa, National Trust, London.

Green, M.J., 1976, A Corpus of Religious Material from the Civilian Areas of Roman Britain, BAR, Oxford.

Green, M.J., 1992, Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend, Thames and Hudson, London.

Green, M.J. (ed.), 1996, The Celtic World, Routledge, London.

Haining, R., 1990, Spatial data analysis in the social and environmental sciences, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Hanson, W.S., 1994, "Dealing with Barbarians: the Romanization of Britain", in Vyner, B. (ed.), Building on the Past: Papers celebrating 150 years of the Royal Archaeological Institute, Royal Archaeological Institute, London, pp. 149-63.

Hingley, R., 1996, "The 'legacy' of Rome: the rise, decline, and fall of the theory of Romanization", in Webster, J. and Cooper, N.J. (eds.), Roman Imperialism: Post-Colonial Perspectives, Leicester Archaeology Monographs, Leicester, pp. 35-48.

Mattingly, D. (ed.), 1997, Dialogues in Roman Imperialism: Power, discourse, and discrepant experience in the Roman Empire, Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series, Portsmouth.

Renfrew, C. and Bahn, P., 1996, Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice, 2nd ed., Thames and Hudson, London.

Renfrew, C. and Shennan S. (eds.), 1982, Ranking, Resource and Exchange: Apects of the archaeology of Early European Society, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Richmond, I.A., 1959, "The Roman Villa at Chedworth, 1958-59", Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 78, pp. 5-23.

Rodwell, W., 1980, "Temple Archaeology: Problems of the Present and Portents for the Future", in Rodwell, W. (ed.), Temples, Churches and Religion: Recent Research in Roman Britain, BAR, Oxford, pp. 211-41.

Rodwell, W. (ed.), 1980, Temples, Churches and Religion: Recent Research in Roman Britain, BAR, Oxford.

St. Clair Baddeley, 1930, "The Romano-British temple, Chedworth", Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 52, pp. 255-64.

Smith, J.T., 1978, "Villas as a key to Social Structure", in Todd, M. (ed.), Studies in the Romano-British Villa, Leicester University Press, Leicester, pp. 149-86.

Smith, J.T., 1997, Roman Villas: a Study in Social Structure, Routledge, London.

Vyner, B. (ed.), 1994, Building on the Past: Papers celebrating 150 years of the Royal Archaeological Institute, Royal Archaeological Institute, London

Webster, G., 1984, "The Function of the Chedworth Roman Villa", Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 101, pp. 5-20.

Webster, J., 1997, "A negotiated syncretism: readings on the development of Romano-Celtic religion", in Mattingly, D. (ed.), Dialogues in Roman Imperialism: Power, discourse, and discrepant experience in the Roman Empire, Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series, Portsmouth, pp. 165-84.

Webster, J. and Cooper, N.J. (eds.), 1996, Roman Imperialism: Post-Colonial Perspectives, Leicester Archaeology Monographs, Leicester.

Whittaker, C.R., 1997, "Imperialism and culture: the Roman initiative", in Mattingly, D. (ed.), Dialogues in Roman Imperialism: Power, discourse, and discrepant experience in the Roman Empire, Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series, Portsmouth, pp. 143-63.

Wilson, D.R., 1959, "Roman Britain in 1958: Sites Explored", Journal of Roman Studies 49, pp. 102-35.

NOTES

1 For further discussion of the association between Romanised villas and temples, see G. Adams, "Who built the rural Romano-Celtic Temples? Lydney and the Chesters Villa: a case study", Melbourne Historical Journal Special Issue: Proceedings of the Mass Historia Postgraduate Conference 2001, 2002, pp. 25-8.

2 S. Clarke, "Acculturation and continuity: re-assessing the significance of Romanisation in the hinterlands of Gloucester and Cirencester", in J. Webster and N.J. Cooper (eds.), Roman Imperialism: Post-Colonial Perspectives, Leicester Archaeology Monographs, Leicester, 1996, p. 83.

3 G. de la Bedoyere, The Golden Age of Roman Britain, Tempus, Stroud, 1999, p. 77.

4 R. Hingley, "The 'legacy' of Rome: the rise, decline, and fall of the theory of Romanisation", in J. Webster and N.J. Cooper (eds.), Roman Imperialism: Post-Colonial Perspectives, Leicester Archaeology Monographs, Leicester, 1996, p. 44.

5 J. Webster, "A negotiated syncretism: readings on the development of Romano-Celtic religion", in D. Mattingly (ed.), Dialogues in Roman Imperialism: Power, discourse, and discrepant experience in the Roman Empire, Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series, Portsmouth, 1997, pp. 166-7.

6 R. Goodburn, The Roman Villa - Chedworth, National Trust, London, 1983, p. 6.

7 I.A. Richmond, "The Roman Villa at Chedworth, 1958-59", Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 78, 1959, p. 6.

8 J.T. Smith, Roman Villas: a study in social structure, Routledge, London, 1997, p. 163.

9 R. Goodburn, Chedworth Roman Villa, National Trust, London, 1998, p. 13.

10 Goodburn, Chedworth Roman Villa, p. 35; S.S. Frere, "Roman Britain in 1990: Sites Explored", Britannia 22, 1991, p. 274. The mosaics were constructed out of red clay and various coloured limestone, laid on three distinct levels of concrete.

11 Richmond, "The Roman Villas at Chedworth, 1958-59", p. 8.

12 M.J.T. Lewis, Temples of Roman Britain, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1966, pp. 1, 13.

13 St. Clair Baddeley, "The Romano-British Temple, Chedworth", Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 52, 1930, p. 258.

14 B. Cunliffe, "Pits, Preconceptions and Propitiation in the British Iron Age", Oxford Journal of Archaeology 11, 1992, pp. 69-83.

15 Goodburn, Chedworth Roman Villa, p. 34.

16 Lewis, Temples of Roman Britain, p. 48.

17 T.F.C. Blagg, "The Decorated Stonework of Roman Temples in Britain", in W. Rodwell (ed.), Temples, Churches and Religion: Recent Research in Roman Britain, Bar, Oxford, 1980, pp. 36, 38.

18 W. Rodwell, "Temple Archaeology: Problems of the Present and Portents for the Future", in W. Rodwell (ed.), Temples, Churches and Religion: Recent Research in Roman Britain, British Archaeological Reports, Oxford, 1980, p. 219.

19 C. Renfrew and P. Bahn, Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice, 2nd ed., Thames and Hudson, 1996, p. 387.

20 A. Gatrell, Distance and Space: a geographical perspective, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1983, p. 35.

21 R. Haining, Spatial data analysis in the social and environmental sciences, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1990, pp. 70-1.

22 Goodburn, Chedworth Roman Villa, p. 34.

23 Cunliffe, "Pits, Preconceptions and Propitiation in the British Iron Age", pp. 69-83.

24 Lewis, Temples in Roman Britain, p. 53.

25 Goodburn, Chedworth Roman Villa, p. 13.

26 Lewis, Temples in Roman Britain, p. 41.

27 Goodburn, Chedworth Roman Villa, p. 13.

28 Anon., "Chedworth Roman Villa", Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 14, 1889-90, p. 215.

29 A large column was also discovered, thrown into the octagonal basin. It may have been part of a pair, supporting the front of the nymphaeum. Goodburn, Chedworth Roman Villa, p. 13; J. Farrer, "Chedworth Roman Villa", Journal of the British Archaeological Association 26, 1870, p. 251.

30 Blagg, "The Decorated Stonework of Roman Temples in Britain", pp. 36, 38.

31 Smith, Roman Villas, p. 291.

32 Cicero, De Legibus, 2.8.19. "They shall approach the gods in purity, bringing piety, and leaving riches behind. Whoever shall do otherwise, God Himself will deal out punishment to him....In cities they shall have shrines; they shall have groves in the country and homes for the Lares" (trans. C. Walker Keyes).

33 Cicero, De Re Publica, 5.5.7. "But, as regards the practical conduct of life, this system provides for legal marriage, legitimate children, and the consecration of homes to the Lares and Penates of families, so that all may make use of the common property and of their own personal possessions. It is impossible to live well except in a good commonwealth, and nothing can produce greater happiness than a well-constituted State" (trans. C. Walker Keyes).

34 Plautus, Aulularia, pro. 18-20. "As a matter of fact, his neglect grew and grew apace, and he showed me less honour. I did the same by him, so he also died" (trans. P. Nixon).

35 K. Dark and P. Dark, The Landscape of Roman Britain, Sutton, Stroud, 1997, p. 48.

36 G.E. Fox, "The Roman Villa at Chedworth, Gloucestershire", Archaeological Journal 44, 1887, p. 323.

37 Goodburn, Chedworth Roman Villa, p. 24.

38 A.S. Esmonde Cleary, "Roman Britain in 1993: Sites Explored", Britannia 25, 1994, p. 285.

39 J.T. Smith, "Villas as a key to Social Structure", in M. Todd (ed.), Studies in the Romano-British Villa, Leicester University Press, Leicester, 1978, p. 162.

40 Smith, Roman Villas, p. 291.

41 Goodburn, The Roman Villa - Chedworth, p. 24.

42 RIB 126.

43 Goodburn, Chedworth Roman Villa, p. 27.

44 M.J. Green, Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend, Thames and Hudson, London, 1992, p. 142.

45 Goodburn, Chedworth Roman Villa, p. 27.

46 M.J. Green, A Corpus of Religious Material from the Civilian Areas of Roman Britain, British Aarchaeological Reports, Oxford, 1976, p. 174.

47 G. Webster, "The Function of Chedworth Roman Villa", Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 101, 1984, pp. 5-20.

48 G. de la Bedoyere, Roman Villas and the Countryside, B.T. Batsford, London, 1993, p. 115.

49 RIB 128.

50 Goodburn, Chedworth Roman Villa, p. 24.

51 Smith, Roman Villas, p. 214.

52 Smith, Roman Villas, p. 289.

53 T. Derks, Gods, Temples and Ritual Practices, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 1998, p. 177.

54 D.R. Wilson, "Roman Britain in 1958: Sites Explored", Journal of Roman Studies 49, 1959, p. 127.

55 C.R. Whittaker, "Imperialism and culture: the Roman initiative", in D. Mattingly (ed.), Dialogues in Roman Imperialism: Power, discourse, and discrepant experience in the Roman Empire, Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series, Portsmouth, 1997, p. 155.

56 Whittaker, "Imperialism and culture: the Roman initiative", pp. 154-5.

57 W.S. Hanson, "Dealing with Barbarians: the Romanization of Britain", in B. Vyner (ed.), Building on the Past: Papers celebrating 150 years of the Royal Archaeological Institute, Royal Archaeological Institute, London, 1994b, p. 155.

Back to Cover

Back to Cover

One of the wealthiest villas in Gloucestershire which does show the distinction between different groups of residents can be found at Chedworth (Fig. I). This villa (SP 052134), one of the most famous Roman sites in Britain, clearly reflects the desire of the native aristocracy for status. The reason for the location of the villa was probably the availability of water, as there was a natural spring in the north-west corner of the complex.6 The original unpretentious villa was established in the early/mid-second century (Fig. II).7 It began as three separate buildings on three sides of a courtyard and was gradually connected.8 The addition of luxurious facilities and the majority of the improvements to the villa occurred early in the fourth century AD.9 The building may have been originally built with timber in the form which it later took in stone, representing a gradual process of Romanization from form to material adaptation. Later in the century, after a destructive fire, it was replaced in an extended form with baths and more rooms (Fig. III). Features included a wealth of decorated walls, stone sculptures, mosaic floors, comfortable heated rooms and bathing facilities.10 These changes reflect the high degree of wealth of the dominant resident, as such additions were notably absent from other sections of the villa.

One of the wealthiest villas in Gloucestershire which does show the distinction between different groups of residents can be found at Chedworth (Fig. I). This villa (SP 052134), one of the most famous Roman sites in Britain, clearly reflects the desire of the native aristocracy for status. The reason for the location of the villa was probably the availability of water, as there was a natural spring in the north-west corner of the complex.6 The original unpretentious villa was established in the early/mid-second century (Fig. II).7 It began as three separate buildings on three sides of a courtyard and was gradually connected.8 The addition of luxurious facilities and the majority of the improvements to the villa occurred early in the fourth century AD.9 The building may have been originally built with timber in the form which it later took in stone, representing a gradual process of Romanization from form to material adaptation. Later in the century, after a destructive fire, it was replaced in an extended form with baths and more rooms (Fig. III). Features included a wealth of decorated walls, stone sculptures, mosaic floors, comfortable heated rooms and bathing facilities.10 These changes reflect the high degree of wealth of the dominant resident, as such additions were notably absent from other sections of the villa.